Researchers at Cardiff University have identified a peculiar twisting motion in the orbits of two colliding black holes, an exotic phenomenon predicted by Einstein’s theory of gravity.

Their study, which is published in Nature and led by Professor Mark Hannam, Dr. Charlie Hoy and Dr. Jonathan Thompson, reports that this is the first time this effect, known as precession, has been seen in black holes, where the twisting is 10 billion times faster than in previous observations.

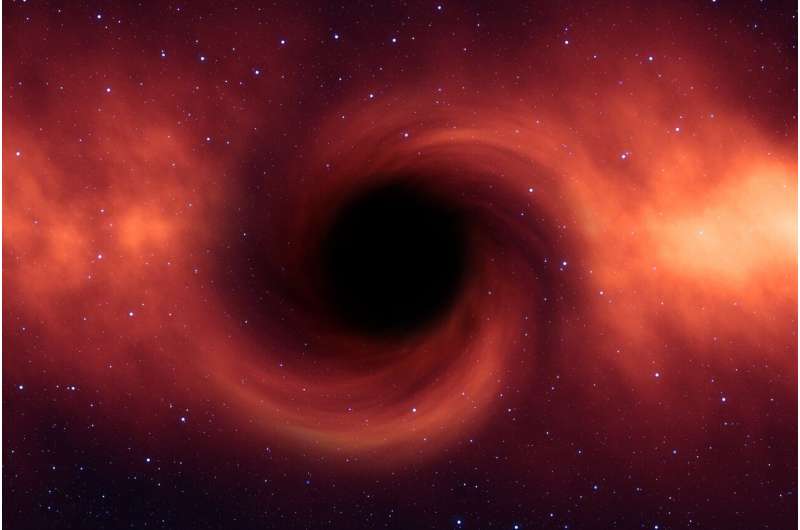

The binary black hole system was found through gravitational waves in early 2020 in the Advanced LIGO and Virgo detectors. One of the black holes, 40 times more massive than our Sun, is likely the fastest spinning black hole to be found through gravitational waves. And unlike all previous observations, the rapidly revolving black hole distorted space and time so much that the binary’s entire orbit wobbled back and forth.

This form of precession is specific to Einstein’s theory of general relativity. These results confirm its existence in the most extreme physical event we can observe, the collision of two black holes.

“We’ve always thought that binary black holes can do this,” said Professor Mark Hannam of Cardiff University’s Gravity Exploration Institute. “We have been hoping to spot an example ever since the first gravitational wave detections. We had to wait for five years and over 80 separate detections, but finally we have one!”

A more down-to-earth example of precession is the wobbling of a spinning top, which may wobble—or precess—once every few seconds. By contrast, precession in general relativity is usually such a weak effect that it is imperceptible. In the fastest example previously measured from orbiting neutron stars called binary pulsars, it took over 75 years for the orbit to precess. The black-hole binary in this study, colloquially known as GW200129 (named after the date it was observed, January 29, 2020), precesses several times every second—an effect 10 billion times stronger than measured previously.

Dr. Jonathan Thompson, also of Cardiff University, explained: “It’s a very tricky effect to identify. Gravitational waves are extremely weak and to detect them requires the most sensitive measurement apparatus in history. The precession is an even weaker effect buried inside the already weak signal, so we had to do a careful analysis to uncover it.”

Gravitational waves were predicted by Einstein in 1916. They were first directly detected from the merger of two black holes by the Advanced LIGO instruments in 2015, a breakthrough discovery that led to the 2017 Nobel Prize. Gravitational wave astronomy is now one of the most vibrant fields of science, with a network of the Advanced LIGO, Virgo and KAGRA detectors operating in the US, Europe and Japan. To date there have been over 80 detections, all of merging black holes or neutron stars.

“So far most black holes we’ve found with gravitational waves have been spinning fairly slowly,” said Dr. Charlie Hoy, a researcher at Cardiff University during this study, and now at the University of Portsmouth. “The larger black hole in this binary, which was about 40 times more massive than the Sun, was spinning almost as fast as physically possible. Our current models of how binaries form suggest this one was extremely rare, maybe a one in a thousand event. Or it could be a sign that our models need to change.”

The international network of gravitational-wave detectors is currently being upgraded and will start its next search of the universe in 2023. They are likely to find hundreds more black holes colliding, and will tell scientists whether GW200129 was a rare exception, or a sign that our universe is even stranger than they thought.