For centuries it was the myth that transfixed fortune-hunters: El Dorado, the dazzling city made of gold, hidden in deepest South America. Countless European bounty seekers lost their lives in search of this legendary place.

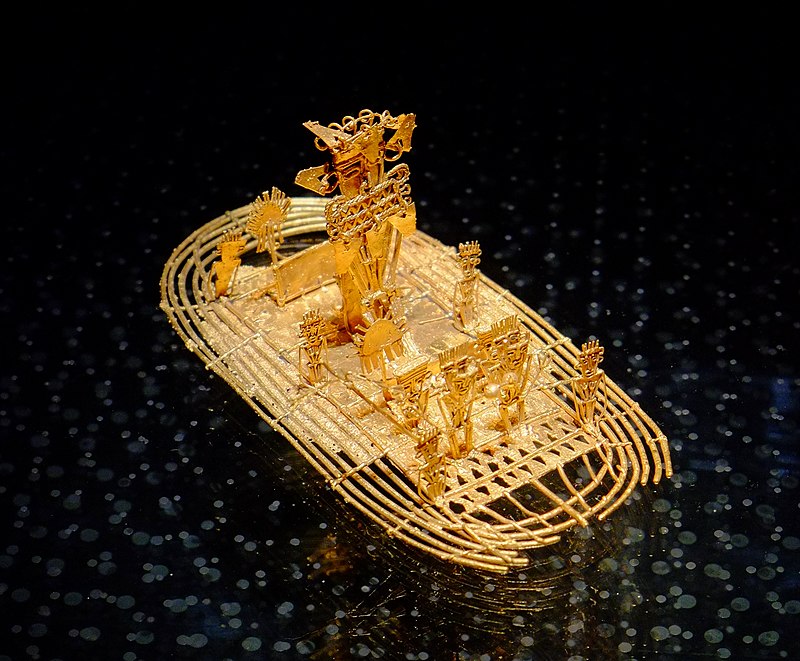

Others believed that El Dorado was not a city at all, but a man painted with powdered gold who had dived into Lake Guatavita, near the modern Colombian capital of Bogota, and whose priceless body lay waiting to be discovered.

Neither the city nor the man was ever found. But as a new exhibition at the British Museum, opening today, shows, European explorers did find an ancient civilisation seemingly obsessed with gold and other precious metals, mined in the Andes.

Prized beast: This flask has been carved in the shape of a Jaguar, and has a nose ring made of platinum

This was a society with its own sophisticated religious, social and musical rites — but also one capable of extreme violence and addicted to the intoxicating coca leaf, the raw material of modern cocaine.

In the new show, 200 objects from the Museo del Oro in Bogota and 100 from the British Museum reveal just how devoted to gold the pre-Hispanic civilisations, from 1600 BC to AD 1600, were.

They didn’t see gold as a currency but as a magical material of great symbolic and spiritual meaning, closely connected to the immense powers of the sun.

Figure of fear: This flask, or ‘poporo’, shows a human face wearing a peacock headdress

One star exhibit in this show is a flask in the shape of a jaguar made from hammered gold sheets — with a platinum ring strung through its nose. Platinum was as prized as gold in ancient Colombia.

In order to make the transition from the human world to the animal one, these pre-Hispanic civilisations also devised golden costumes.

‘Birds, bats, felines, amphibians, snakes and alligators were just some of the powerful disguises adopted,’ says Elisenda Vila Llonch, the curator of the show.

Sitting pretty: This female figure, left, which would have been used for holding lime powder, features in the exhibition alongside this religious chest ornament, right

‘Representations of these animals were frequently made in elaborate gold pieces.

‘Gold objects, including nose, lip and ear ornaments, diadems [ornamental headbands], pectorals [decorations worn on the chest] and pendants enabled a person’s physical transformation, together with paint, animal pelts and feathers.’

They used gold, too, to contain their favourite narcotic stimulants from plants including tobacco, cocaine and the yopo — a tree that produces leaves and beans with hallucinogenic effects.

On show at the British Museum is a huge, egg-shaped shell of gold alloy, 21.4cm long and 10.5cm wide.

Finery: The pre-Hispanic people used gold for all sorts of ornaments, including this necklace

This priceless artefact was made purely for the purpose of holding coca leaves. Another exhibit shows a man sitting down in a state of blissful leisure, chewing on a wad of the same leaves.

The pre-Hispanic civilisations became extremely adept at drug-taking. In order for the stimulants to be absorbed better, they were combined with a chalky powder made from lime and smashed seashells.

Delicately carved golden dippers — like pipettes — were used to carry the intoxicating powder from elaborate drug pouches to the mouth. At other times they used gold snuff trays — like ornate mini-shovels — piled high with dried or crushed yopo seeds, which they then swallowed or sniffed.

By taking these intoxicating substances, the men of this ancient civilisation believed that their spirits might leave their bodies — just as they did through the wearing of animal skins.

Dazzling: An alligator pendant. Powerful creatures were revered and often crafted from gold

A priest told one of the first Spanish colonials that, under the influence of yopo beans, he had ‘flown’ a vast distance to and from the distant village of Santa Marta in a single night. So the idea of the drug trip is certainly nothing new.

But the world of El Dorado was far from being a zonked-out, peace-and-love civilisation.

Many of the gold objects in the British Museum exhibition are devoted to warfare, including spear-throwers — sheaths in which a spear was placed before it was hurled, to give it greater reach.

One tunjo — or religious figurine — in the exhibition shows a small golden figure at work on the most spine-chilling of activities: headhunting.

Grisly: This figure shows a headhunter carrying a shrunken head

In one hand he holds a bow and arrows, in the other the shrunken head of his victim. Two other tunjos show a pair of dead victims tied to sacrificial poles.

Headhunting is thought to have been a common practice in warfare, and these tunjos are supposed by experts to symbolise victory on the battlefield over rival tribes.

The 16th-century Spanish chronicler Gonzalo Fernandez de Oviedo y Valdes described the ritual, saying: ‘If the men of Bogota kill or take any Panches Indians prisoner, they take the heads back to their homeland and put them in their oratories [or prayer chapels].’

Mask: This artefact may have been stored away for use in the afterlife

The story is first mentioned by Fernandez de Oviedo in his history of the region, written from 1535 to 1548.

Oviedo tells of a ‘golden king’ who ‘went about covered with powdered gold, as casually as if it were powdered salt’.

Intricate: This golden helmet has been elaborately patterned by ancient craftsmen

It was believed that these treasures would reach the gods, who would restore order to the world.