“They were under a lot of business pressure … they were willing to do anything.”

Twenty-one years ago, when Seeni was just a baby, she lived in the wild with her family in the Kruger National Park region of South Africa. But her life drastically changed when the country killed Seeni’s family during an organized cull, which was done to protect vegetation, and to supposedly strengthen biodiversity in the area.

Park officials didn’t discriminate when they killed elephants during these culls — they killed the oldest matriarchs as well as the youngest calves. But somehow, Seeni survived. However, Dr. Toni Frohoff, a behavioral and wildlife biologist and elephant campaign director for In Defense of Animals, believes Seeni would be dealing with a great deal of trauma.

But Seeni had no time to grieve. Shortly after the cull, she was moved to a privately-owned nature reserve in Botswana, where she and three other elephants were on public display and forced to give people rides. When Seeni got a little older, the trainer moved her to another camp with the goal of breeding her with a wild male elephant. It didn’t take long for Seeni to get pregnant.

In 2011, Seeni’s life changed again. The International Conservation Center (ICC), which promotes itself as a “conservation, research, education, breeding, and training facility” and is part of the Pittsburgh Zoo, paid to ship Seeni and two other female elephants from Botswana to Pennsylvania.

“Seeni’s pregnancy is exciting news,” Dr. Barbara Baker, president and CEO of Pittsburgh Zoo, told WTAE in 2017. “The infusion of new genetics is important to secure a future for African elephants in North America.”

“The fact that she [Seeni] was known to have exhibited neglect to a previous calf indicates … apparent behavior that is indicative of an underlying trauma, as well as raising concerns about how appropriate it is for her to be used for reproduction,” Frohoff told The Dodo. “In fact, some professionals would argue that it was reckless and selfish of the facilities to impregnate Seeni.”

Facebook/Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium

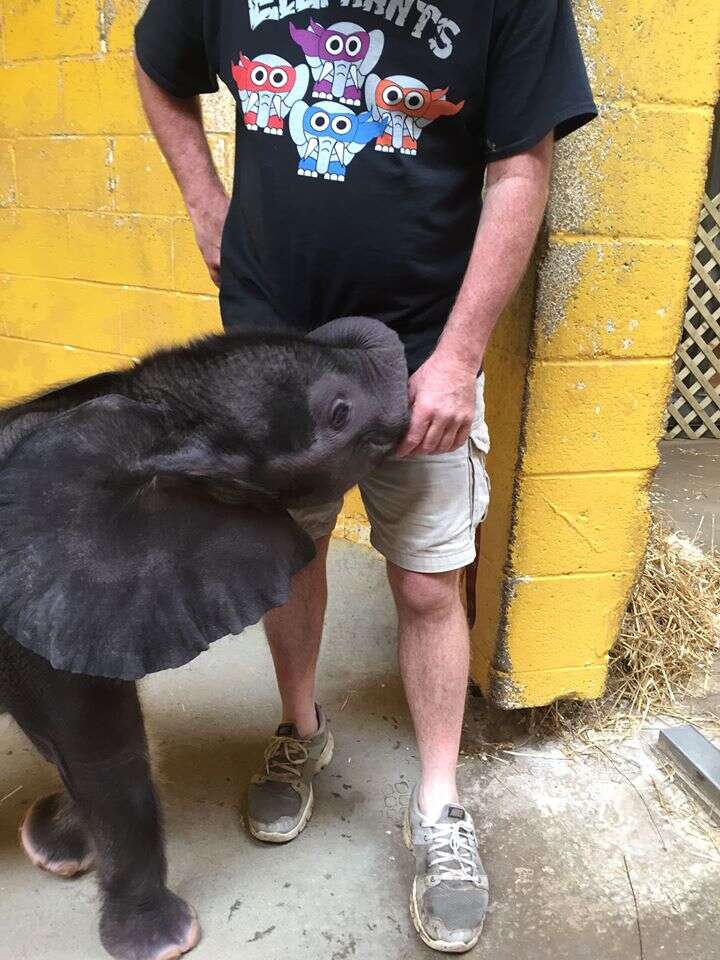

According to media reports, Seeni wasn’t producing milk for her calf, so the ICC staff decided to remove the baby from her mother and take the baby to the Pittsburgh Zoo, where human caretakers would hand-rear her and feed her milk with a bottle.

Not long after being separated from her mom, the baby (who remains unnamed) became critically ill. She stopped feeding and lost 15 pounds.

“If this baby survives, she will not have the maternal skills needed either to successfully reproduce,” Frohoff said. “So what they are doing is breeding successive generations of psychologically impoverished elephants, which in the opinion of many conservation biologists is irresponsible. She [the baby] has already suffered the absence of her mother … but she’s also suffering both psychologically and mentally from these invasive medical procedures.”

Facebook/Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium

After being moved to the Pittsburgh Zoo, the weak baby elephant was almost immediately placed on display for the public, which Frohoff believes was an effort to bring in more visitors and money to the zoo. “It’s very profitable for them,” she said.

While Frohoff is particularly concerned for the health and well-being of Seeni and her baby, she points toward a larger issue at hand — the zoo’s treatment of elephants as objects, rather than as sentient beings.

Facebook/Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium

“The old paradigm that appears to be being used is that elephants are mere objects, while ignoring all of the scientific evidence to the contrary that they are sentient individuals and complex social cultures that then create what is an elephant,” Frohoff said. “They [zoos] are not considering that what makes an elephant an elephant is a rich and complex psychological and cultural way of being in the world, and if you take away their cultural identity [and family] … you are creating, through that process, an extremely unnatural elephant that cannot be expected to reproduce successfully.”

Pittsburgh Zoo could not be immediately reached for comment.

Faecbook/Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium

The best solution for Seeni and her baby would be to send them both to a certified elephant sanctuary, Frohoff explained, although she added that the baby would first need to be stabilized, and the right time for such a move would need to be properly assessed.

“It wouldn’t be surprising if Seeni and the baby would bond more easily with Seeni in a healthier environment where she wasn’t being chronically and institutionally traumatized as she is at Pittsburgh Zoo,” Frohoff said.

Another way to help elephants like Seeni and her baby is to support organizations that help keep them in the wild, Anderson said.

Facebook/Pittsburgh Zoo & PPG Aquarium

“Take the money you would spend going to a zoo, and donate it to an African organization that is helping to protect wild elephants,” Anderson said. “It’s really maddening to see zoos suck up so much money from the public and spend so much money on captivity, when all of that should be going to elephants in Africa and Asia and the people who are protecting them there.”