Liquid heat rises in waves, twisting and turning morphing the parked T-37 Tweety Birds into caricatures more like reflections in a fun house than the small jet trainers that introduced countless thousands of potential pilots to jet-powered flight. I could almost feel the rubber soles on my boots beginning to melt. Okay, that’s a bit of an exaggeration, but the temperature is uncomfortable. As my student and I step up to the little jet, we are assaulted by the familiar T-37 smell: hot rubber, avgas, and the underlying sour odor of vomit—NASA’s “Vomit Comet” has nothing over the T-37’s propensity to induce airsickness in the toughest of students.

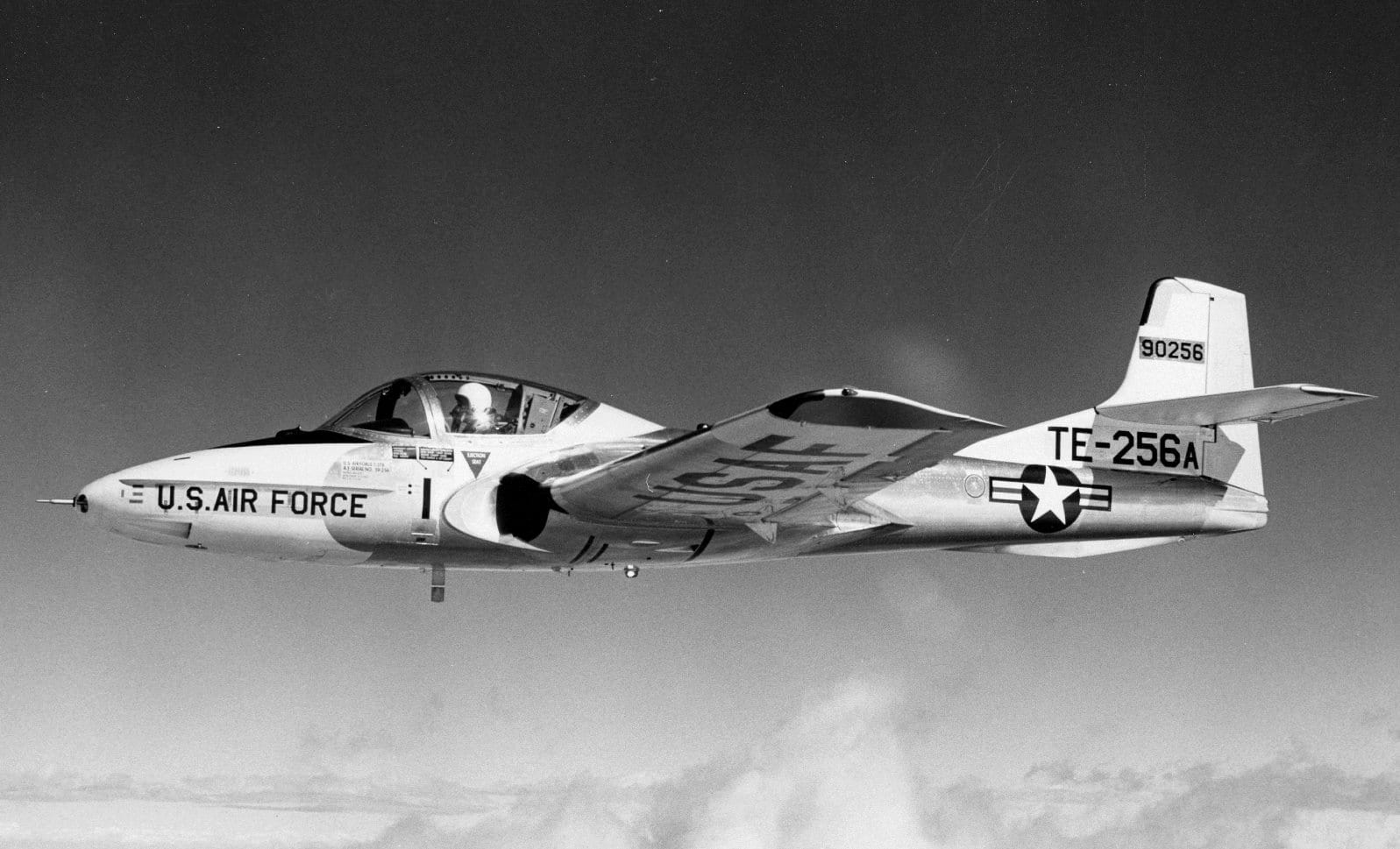

A friend once observed that the combination of heat, nervousness, confinement in an ejection seat, helmet, oxygen mask, and the loping flight characteristic of the T-37—much like a twin-engine propeller aircraft flying with the engines out of sync—did wonders to convince the internal “pukester” to go to work. Regardless, the versatile little Cessna was the Air Force pilot training work horse from 1956, when the Air Force took delivery of the first of 444 T-37s, until the last was retired in 2009. But the T-37 had more uses than a primary jet trainer.

A Bit of Background

DAYTON, Ohio — Cessna YA-37A Dragonfly at the National Museum of the United States Air Force. (U.S. Air Force photo)

During the Vietnam War, a modified T-37 with more powerful engines, a weight increase from around 6,000 pounds to 12,000 pounds, an ordinance carrying capacity of approximately 2,000 pounds, and a new designation, replaced the A-1 Sandy as the Air Force search and rescue aircraft. In this capacity, the Dragonfly worked with the Jolly Greens to rescue downed pilots by keeping the enemy at bay until the rescue helicopters could retrieve the downed pilot.

In 1962, Cessna suggested the T-37 replace the F-100 as the platform for the Thunderbirds, the Air Force aerobatic demonstration team[2]. The Air Force could not imagine the 6000-pound dog whistle living up to the name, Thunderbird. They elected to keep the F-100 and its thunderous roar as the team aircraft, and in the process, probably saved themselves from smirks and eye rolling when the whistling little “Thunderbird” passed over the spectators. Of course, the Air Force had itself to blame for the T-37’s whistling.

The Air Force’s made the decision to use the noisier of two government supplied engines to power the jet. Harry Clements, an engineer that worked on the T-37 design, says Cessna put vanes and sound proofing on the inlets that damped the noise to a tolerable level, but the Air Force felt the whistling was more acceptable than the loss of performance, so the noise limiting materials were discarded[3] much to the discomfort and hearing loss of a long line of Tweet pilots.

Dollar Ride

Of course, my student doesn’t care about any of these T-37 facts. His only concern is getting through his “dollar ride” (his first T-37 student flight) without embarrassing himself. As I demonstrate the walk-around preflight inspection, my student demonstrates a mixture of “dollar-ride” excitement and first-flight apprehension. I switch on my best calming voice to help relieve the stress. I remember my instructor, in a fit of frustration, jerking my oxygen hose yelling, “Why don’t you SIE?” In other words, why don’t you self-initiate your elimination from the program.

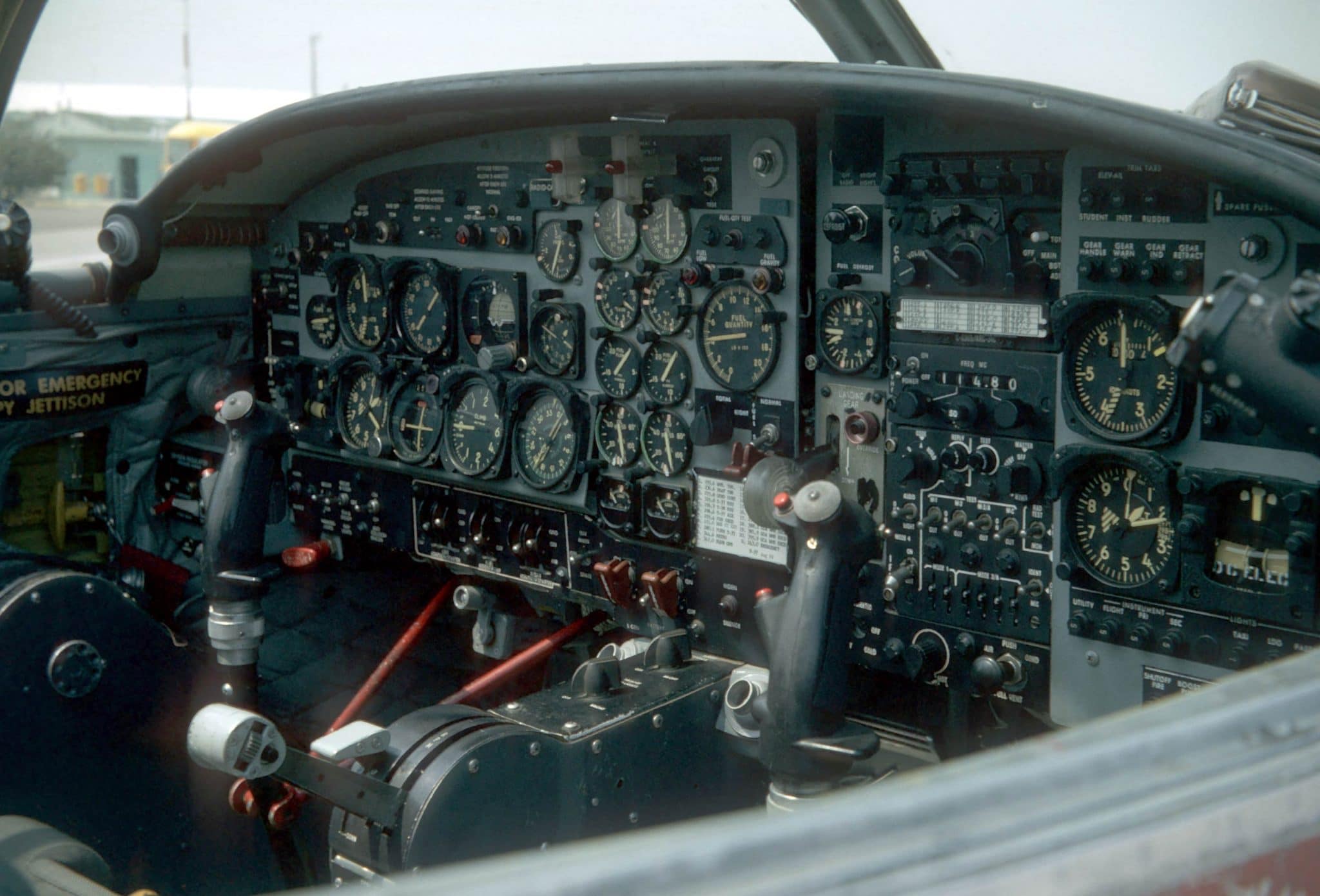

A visual testament to instructor frustration is etched into the instrument panel glare shields of the little trainers. The glare shields in the T-37 were awash in repairs from damage done by instructors pounding on and breaking the material. I never saw the point myself.

We are strapped in, I demonstrate the interior preflight, start engines, show the ground crew the seat pins, and begin to taxi. Student’s react to this moment in differing ways. Some are struck with a bout of oral diarrhea; some become mute. My guy is mute. I get takeoff clearance, close the clamshell canopy and transition from a convertible to a greenhouse, roll onto the runway, and apply power. My goal is to get into the reasonably cool air above 10,000 feet as soon as possible.

As I raise the landing gear, I glance at my student. He is encapsulated behind mask and sunshade. I see him swallowing; I fear things are going to blow. I intercede and give him the stick. It starts to cool off, and the distraction of flying has cooled off my student.

“Wow, this is something,” he says.

“It sure is,” I say. “And it only gets better.”