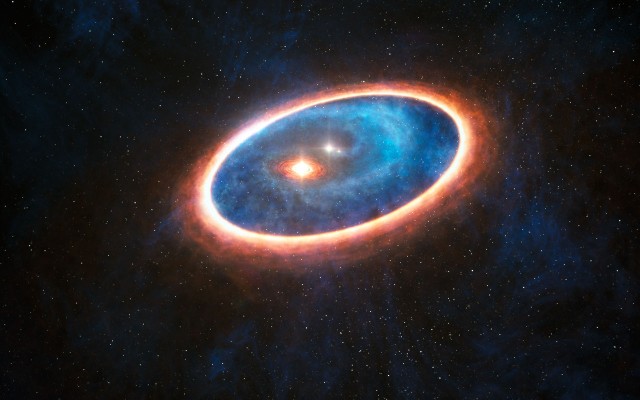

A star ballet is taking place somewhere in the depths of our universe.

Three gigantic, brilliant stars are caught in a dance by their own gravitational forces and aglow in their shared radiance against the dark veil of space. Two fiery balls of gas are pirouetting closely around each other, completing their mutual orbit to the beat of an Earth day. At the same time, a third star steadily encircles the two, shining a light on their performance.

Details on the cosmic predicament can be found in a study published in the Royal Astronomical Society’s Monthly Notices in June.

“As far as we know, it is the first of its kind ever found,” Alejandro Vigna-Gomez, a co-author of the article and an astronomer at the University of Copenhagen, said in a statement Monday.

According to Vigna-Gomez, we know of many secondary star systems, but they are not just far farther away than this sparkling trio, but they are also often less massive. By a long shot.

The interior, close-quarter binary stars have a combined mass of around 12 times that of our sun, while the wide-field globe encircling them has a mass of 16 times that of our sun. To put this in context, it would take more than 330,000 Earths to equal one solar mass, which is 99.8% of the mass of our entire solar system. Simply simply, these incredible ballerinas are massive.

In the broader scheme of things, however, Vigna-Gomez was after far more than just detecting this remarkable starry pattern. The goal was to figure out how such a ferocious triplet – formally known as TIC 470710327 – came to be.

A ballerina has gone missing.

Vigna-Gomez and colleague Bin Liu, a theoretical astrophysicist also affiliated with the University of Copenhagen, first proposed numerous scenarios for the newly discovered three-star system’s origins.

First and foremost, there was the notion that the larger, outer star originated first. However, after considerable analysis, the scientists recognised that such a stellar leviathan would have most likely thrown material inward, disrupting the double stars’ formation. There would have been no need for a trio. Gaseous rubble would have rained down in all directions.

Second, the scientists investigated the possibility that the binary star dancers and third star spectator formed separately, far apart, and subsequently collided due to some force of gravity. Though this situation has not been completely ruled out, the experts believe it is not the greatest option. They are far more focused on the final and desired option. A little less collaborative.

What if two distinct binary star systems formed near one other, then one of those pairs fused into a huge star, the researchers wondered? If this is correct, the enormous combination star would be the one we see today, orbiting the smaller – but still large – stars within.

In other words, it’s feasible that a fourth dancer was part of this cosmic ballet but was devoured by its own partner before the climactic scene. This was the most likely case, according to the team’s latest research, which was based on tonnes of computer models and fascinatingly anchored in the discoveries of citizen scientists.

“But a model is not enough,” Vigna-Gomez said, arguing that to prove his and Liu’s suspicion with high certainty would require either using telescopes to study the tertiary system in better detail or statistically analyzing nearby star populations.

“We also encourage people in the scientific community to look at the data deeply,” Liu said in a statement. “What we really want to know is whether this kind of system is common in our universe.”

Reference(s): Royal Astronomical Society’s Monthly Notices