Fossilized backbone suggests that the ancient predators were about 2 meters long at birth

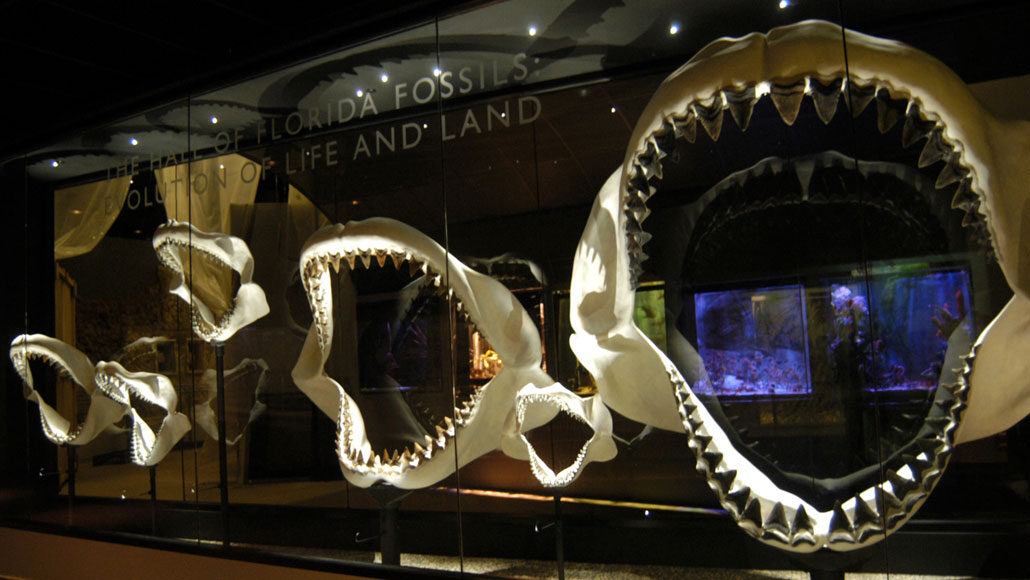

Massive megalodon sharks, whose open jaws (reconstructions shown) could span up to 3 meters, were terrors of the seas, even at birth.

“Baby shark” has taken on a whole new meaning. Newborn megalodon sharks were supersized fish larger than most adult humans, a new study suggests.

An analysis of the growth rates of the ancient ocean predators, which lived between about 23 million and 2.5 million years ago, estimates that the sharks started life at about 2 meters long, researchers report January 11 in Historical Biology.

Otodus megalodon is right up there with Tyrannosaurus rex in the pantheon of scary extinct predators, but little is actually known about the shark’s biology (SN: 8/10/18). Its skeleton was made of difficult-to-fossilize cartilage, so what scientists do know mostly comes from fossilized teeth. For example, paleobiologist Kenshu Shimada of DePaul University in Chicago and colleagues previously used megalodon teeth, as well as those of other ancient and modern sharks, to estimate a total adult body length for the fish of at least 14 meters (SN: 10/5/20).

In the new study, Shimada and colleagues had an extra, rare piece of evidence: megalodon vertebrae. Although shark skeletons are made of cartilage, the animals’ backbones can become hardened and strengthened by deposits of calcium salts, which can then be fossilized. These vertebrae also preserve annual growth bands, like the rings of a tree, showing how the fish grew.

The researchers used an imaging technique called micro-computed tomography to study three well-preserved vertebrae from one shark. Those images revealed 46 growth bands, suggesting that this shark lived to the ripe old age of 46. The creature is estimated to have been about 9 meters long at its death, and the size of the bands hints that the animal grew at a rate of about 16 centimeters each year. That means that the shark would have been about 2 meters long at birth — large enough for even a newborn to be a fearsome foe in the seas, the scientists conclude.

Shimada’s team has previously suggested that while in utero, megalodon sharks, like some of their modern cousins, might have fed on unhatched eggs in the womb. That practice may have helped the giant fish to gain such a large size even before entering the world.