A new kind of ‘Godzilla’ planet – so-called because of its huge size – has been discovered 560 light years from Earth, raising hopes of finding rocky worlds that could sustain life.

Named Kepler-10c, the planet is 17 times more massive than our planet, and has been named a ‘mega-Earth’.

Astronomers didn’t believe such a world could exist because they believed anything so large would grab hydrogen gas as it grew and become a gaseous ‘mini-Neptune’.

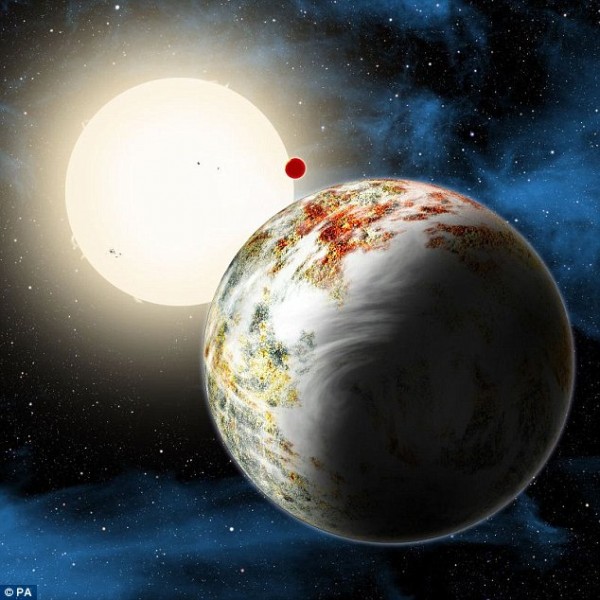

A new kind of ‘Godzilla’ planet – dubbed a mega-Earth – has been discovered in a distant star system. Pictured is an artist’s impression of the newly discovered planet, which dominates the foreground. Its sibling, the lava world Kepler-10b, is in the background

But to their surprise, Kepler-10c has been able to remain solid despite being more than twice as old as the Earth.

The discovery suggests that potentially life-bearing rocky planets may be far more common than first thought, and some could be extremely ancient.The Kepler-10 star system is thought to be 11 billion years old, meaning it formed less than three billion years after the birth to the universe.

Earth, by comparison, is only around 4.5 billion years old.

‘This is the Godzilla of Earths. But unlike the movie monster, Kepler-10c has positive implications for life,’ said Dr Dimitar Sasselov, from the Harvard Smithsonian Centre for Astrophysics (CFA).

‘Finding Kepler-10c tells us that rocky planets could form much earlier than we thought. And if you can make rocks, you can make life.’

Kepler- 10c isn’t likely to harbour life as it is too close to its parents star. Gravity at the surface is about twice that of Earth’s gravity.

The planet circles its sun-like parent star, located in the constellation Draco, every 45 days.

It has at least one unusual neighbour, Kepler-10b – a scorching hot ‘lava world’ three times heavier than Earth that whips around the star once every 20 hours.

The planet was originally spotted by Nasa’s Kepler spacecraft, which finds planets using the transit method – looking for a star that dims when a planet passes in front of it.

By measuring the amount of dimming, astronomers can calculate the planet’s physical size.

Kepler-10c, which has a diameter more than twice that of the Earth, was previously thought to fall into the category of ‘mini-Neptune’ planets that have an icy core surrounded by a thick gassy envelope.

But observations made from the Italian Galileo National Telescope in the Canary Islands confirmed that it has 17 times the mass of the Earth – far heavier than expected.

This proved it must be made from dense rocks, like the Earth.

‘We were very surprised when we realised what we had found,’ said astronomer Dr Xavier Dumusque, also from the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics, who led the research.

‘Kepler-10c didn’t lose its atmosphere over time. It’s massive enough to have held onto one if it ever had it – it must have formed the way we see it now.’

CFA astronomer Lars Buchhave believe he has found a correlation between the period of a planet – how long it takes to orbit its star – and the size at which a planet transitions from rocky to gaseous.

This suggests that more mega-Earths will be found as planet hunters extend their data to longer-period orbits.

The early universe contained only hydrogen and helium. Heavier elements needed to make rocky planets, such as silicon and iron, had to be created in the first generations of stars.

When those stars exploded, they scattered the crucial ingredients through space, which then could be incorporated into later generations of stars and planets.

The process should have taken billions of years, but Kepler-10c shows that the universe was able to form such huge rocks even during the time when heavy elements were scarce.

Professor Sasselov said astronomers should not rule out old stars when they search for Earth-like planets.

And if old stars can host rocky Earths too, he said, then we have a better chance of locating potentially habitable worlds in our cosmic neighborhood.

Kepler- 10c was originally spotted by Nasa’s Kepler spacecraft (artist’s impression pictured), which finds planets using the transit method, looking for a star that dims when a planet passes in front of it. By measuring the dimming, scientists can calculate the planet’s physical size