The tomb of Tutankhamun revealed a wealth of anomalies, beginning with its discovery in 1922, right through the subsequent years of its excavation. The plethora of mysteries that surround the boy king’s mummification and royal burial have endured for nearly a century, from the time they were first noted by the assiduous archaeologist, Howard Carter.

We know the most famous puzzle of them all—the abnormal and excessive use of large amounts of a black, resinous liquid that was liberally poured on the coffin and over the body of the deceased pharaoh. As a result, the mummy was terribly degraded by a chemical reaction caused by these oils and unguents that were intended to regenerate the dead body. Additionally, there exists evidence that this liquid was twice poured into Tutankhamun’s skull after the brain was removed. In all, it has been estimated that the mummy’s skin and wrappings were coated with a staggering 20 liters (5 gallons) of embalming oils―an exceptional amount.

In October 1925, Carter observed, “The most part of the detail is hidden by a black lustrous coating due to pouring over the coffin a libation of great quantity.” Upon unwrapping the mummy, he was moved to describe the corpse as a “charred wreck”. At various places in the tomb, the British archeologist also found lightly wrapped packets of linen “like soot” and “charred powder.”

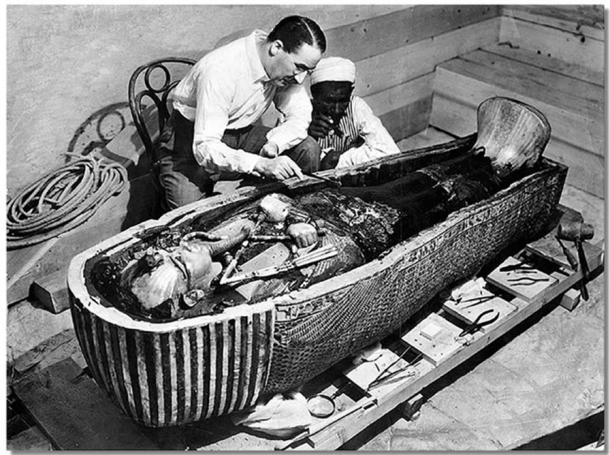

Howard Carter opens the innermost shrine of King Tutankhamen’s tomb near Luxor, Egypt. ( Public Domain )

That the mummy seems to have been suspended upside down for a period is also extremely strange; the X-rays of the skull show unguents solidified in a level consistent with being allowed to settle for some time. The whole burial process seems to have been carried out in a very unusual and slipshod manner. Surely, the tumult of Tutankhamun’s lifetime seems to have followed him into his tomb.

Tutankhamun Mummy Replica, Upper Body and Head. (Flickr/ CC BY-SA 2.0 )

All this is quite odd, because the art of mummification had reached its zenith in the illustrious 18th Dynasty. Some of the finest examples of preservation that serve as a tribute to the ancient embalmers’ skill occurred in that era. Scholars, beginning with Carter himself, have opined that the use of the black liquid was part of an intentional plan to depict Tutankhamun as Osiris, the god of the underworld, “… dark with the rich soil of the inundation, and the source of fertility and regeneration,” according to renowned mummy expert and professor of Egyptology at the American University in Cairo, Salima Ikram.

Heralding the Underworld

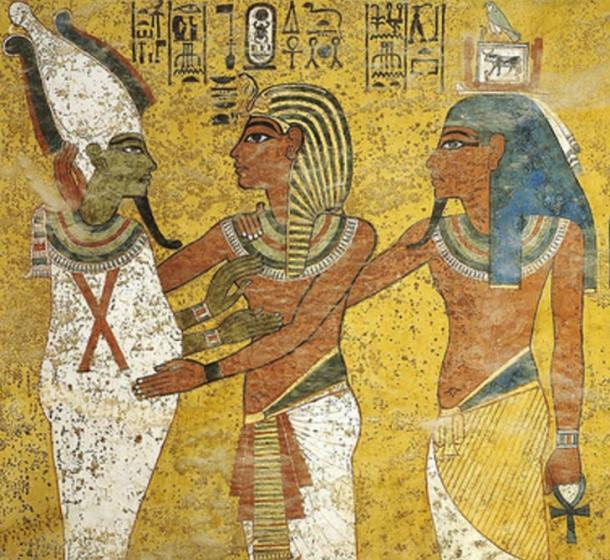

There exists a strong case for such theorization because the art on the north wall of the boy king’s burial chamber depicts him as Osiris. This iconography is to be found in no other tomb in the Valley of the Kings; because the paintings always show the deceased ruler either being welcomed by Osiris in the afterlife; or in the act of making offerings to the deity—never as the god himself. Further proof for this can be had from the way in which Tutankhamun’s arms are positioned; they are not crossed high on his chest as in traditional royal mummies, but very near his waist, such that his protruding elbows mimic the posture of Osiris.

Detail; Pharaoh Tutankhamun embracing god Osiris, scene from the tomb of Tutankhamun, KV62. ( Public Domain )

By all counts, this “fixation” to portray the young pharaoh as Osiris could well have been an overt and physical means of declaring to the gods that the ancient religious order had been restored; considering that Tutankhamun had himself presided over the dismantling of Akhenaten’s doomed religious experiment.

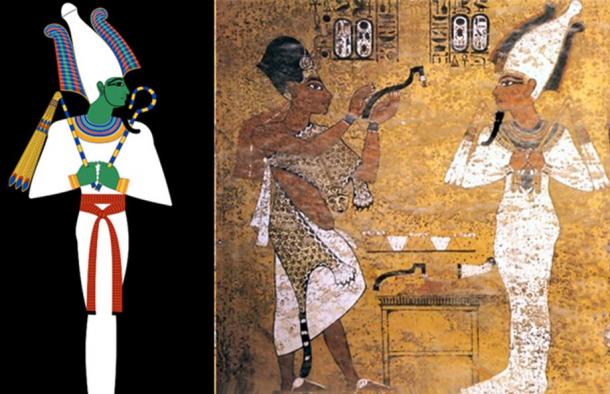

Left, depiction of Egyptian god Osiris. Right, Opening of the Mouth ceremony, Tutankhamun depicted as Osiris. (Public Domain)

These possibilities, speculations, and discrepancies aside, the mother of all mysteries is the case of the teenager’s missing heart. The ancient Egyptians considered the heart a vital and highly valued organ. Why? Because they believed it was the seat of learning, emotions―and more importantly, thought.

Explaining this, Dr. Bob Brier, the world’s foremost expert on human mummies says, “That’s why on Valentine’s Day you send chocolate hearts and not chocolate brains,” and adds, “The Egyptians were resurrectionists. They believed your body would literally get up and go in the next world. So you had to have a complete body, including your internal organs.”

The Heart of the Matter

Even though the four extravagantly decorated golden canopic coffinettes contained the king’s viscera, there was no sign of his heart. Generally, the heart was separately embalmed and placed back in the body. This procedure was not followed in Tutankhamun’s embalming. However, we know that at times a heart scarab was placed in the body, in the absence of the real organ.

A canopic coffinette of king Tutankhamun. It was discovered from his intact KV62 tomb. ( CC BY-SA 2.0 )

The fact that Carter had found an unmolested nest of coffins, beneath a granite lid that weighed a ton and a quarter, negated the possibility of the tomb robbers who had breached the sealed doorway to the sepulchral chamber in antiquity having made away with the heart scarab. Sir Winston Churchill’s observations in an entirely different context serve to explain this baffling situation perfectly, for it is no less than “a riddle wrapped in a mystery inside an enigma.”

A heart scarab on a necklace. ( CC BY 2.0 )

However, the body was not without a scarab, for on the outer bandages of the mummy, above the golden hands and regalia suspended with pieces of gold mummy bands was a large black resin scarab (Carter object 256a) upon a decorated and inscribed gold base scarab. But this scarab ought to have been placed where the heart is located – within the body cavity – and certainly not in the outer wrappings, close to the navel. The smaller scarab, Carter object 256q, was found under the outer wrappings and in the correct position for a heart scarab. Again, not inside the body.

In a documentary titled ‘Tutankhamun: The Mystery of the Burnt Mummy’, Chris Naunton, Director of the Egypt Exploration Society, set out to investigate the perplexity behind the boy king’s death. The usually perfect process of mummification that allowed bodies of the deceased to be preserved for all eternity had somehow been botched up in Tutankhamun’s case.

What Naunton’s research revealed was staggering―the oils used on the pharaoh’s body had combined with the linen of the shroud and oxygen inside the casket, resulting in a fiery combustion! But could only the heart have suffered the ill-fate of being reduced to ashes in such a chemical reaction?

Salima Ikram postulates in her research paper, ‘Some Thoughts on the Mummification of King Tutankhamun’: “The absence of the heart is far more serious. However, some of the publicly available CT-scans do show a space or absence which might have once been where the heart was located. If the heart had been lost by the embalmers, it would be likely that they would make some effort to provide a stand-in, made from linen and resin, or some other material, as is seen when extremities are lost in other mummies, though doubtless this would be done discreetly. If the heart were lost due to the manner in which Tutankhamun died, then there is even more reason for a significant (and visible) heart substitute to have been provided, unless the heart was deliberately removed for a more sinister purpose, or was tied in to a novel method of mummification with a slightly different theological/ideological stress than that used before. Tutankhamun appears to have neither the heart intact, nor a scarab specifically placed on the left side of the chest that would serve as a substitute and insurance for a safe passage to the hereafter. Additionally, neither Burton’s photographs nor Carter’s narrative record a traditional style of heart scarab located directly over the heart.”

However, Egyptologist Sofia Aziz, who differs with this belief, posits that the heart was not always left in the mummy. Reflecting on her research paper titled ‘Mummification: all heart, no brain?’ she states, “This is a common misconception. The brain was also not always removed. A recent study found several mummies without a heart, or an amulet to replace the heart. We don’t actually know what was done with the brain or heart that was removed. There’s still a lot to learn about mummification, but most importantly Tutankhamun’s mummy was not unique in not having a heart. The argument is that a pharaoh’s heart would surely have been left in the mummy for the afterlife; but then, this should have been the case for all Egyptians, as everyone wanted to live on in the after death… it’s confusing why mummification varies so much.”

In an effort to solve this conundrum one must turn to the great legend of Osiris. We are informed in this story that Seth, the evil brother, brutally cut the body of the god into several pieces, ripped his heart out and buried the severed parts in locations across the land. So, was Tutankhamun’s post-embalmment appearance an allusion in action?

If Tutankhamun was responsible for restoring the old gods and this indeed served as a re-enactment of the Osiris myth, is it possible his heart is buried at the cult center associated with Osiris’s heart, or even at Abydos, where one of his main cult centers was?

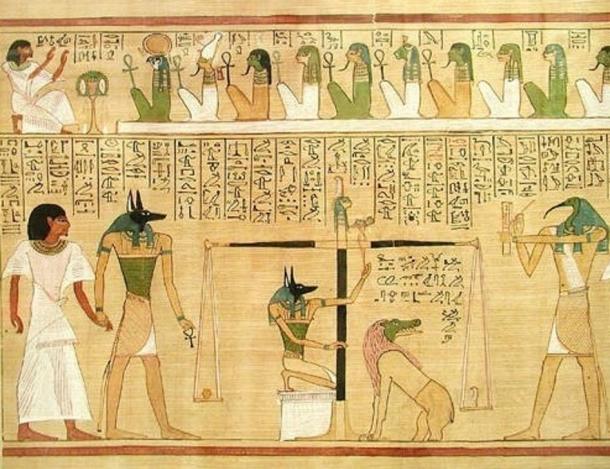

Somehow the pieces don’t seem to fit, and that’s because the Book of the Dead lays extraordinary emphasis on one of its prime aspects, the Weighing of the Heart ceremony, in which the heart of the deceased was weighed against the feather of truth, representing the goddess Ma’at, to determine if the person had earned the right to resurrection.

The “weighing of the heart,” from the book of the dead of Hunefer. Anubis is portrayed as both guiding the deceased forward and manipulating the scales, under the scrutiny of the ibis-headed Thoth. ( Jon Bodsworth )

Live, Forevermore

So what became of Tutankhamun in the afterlife? If one goes by traditional beliefs, he might not even have made it to the crucial part in his journey beyond. Was this child of Amarna the victim of a devious ploy by forces in the Amun priesthood that sought to deny him eternal life?

Did someone purposefully decide that the unfortunate boy king deserved this fate, and that there was no need for “Causing His Name to Live” forever? If true, it was the ultimate damnation inflicted on the pitiable child.

But in keeping with the ardent ancient Egyptian wish to be remembered forever—Nebkheperure, Tutankhamun has lived on down to this day; for we speak his name more than that of any other pharaoh who came before or after him.