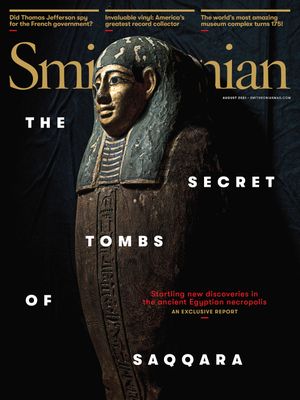

Beneath the ruins of the Bubasteion temple, archaeologists discovered “megatombs” crammed with burials. The coffins pictured date to more than 2,000 years ago. Roger Anis

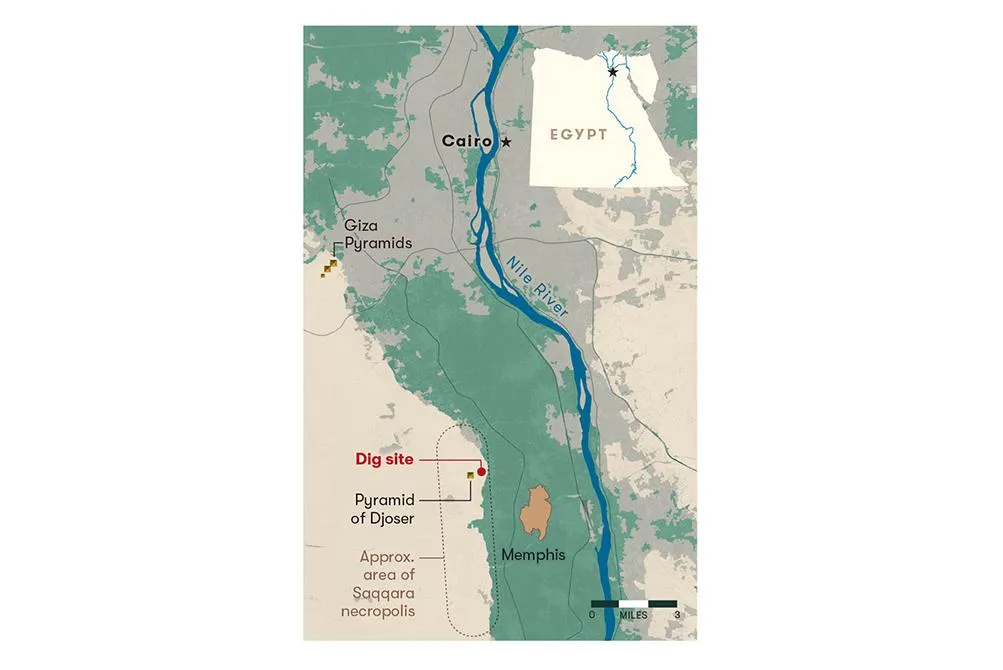

Twenty miles south of Cairo, on the Nile’s west bank, where riverfed crop fields give way to desert, the ancient site of Saqqara is marked by crumbling pyramids that emerge from the sand like dragon’s teeth. Most striking is the famous Step Pyramid, built in the 27th century B.C. by Djoser, the Old Kingdom pharaoh who launched the tradition of constructing pyramids as monumental royal tombs. More than a dozen other pyramids are scattered along the five-mile strip of land, which is also dotted with the remains of temples, tombs and walkways that, together, span the entire history of ancient Egypt. But beneath the ground is far more—a vast and extraordinary netherworld of treasures.

This article is a selection from the July/August issue of Smithsonian magazine

One scorching day last fall, Mohammad Youssef, an archaeologist, clung to a rope inside a shaft that had been closed for more than 2,000 years. At the bottom, he shined his flashlight through a gap in the limestone wall and was greeted by a god’s gleaming eyes: a small, painted statue of the composite funerary deity Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, with a golden face and plumed crown. It was Youssef’s first glimpse of a large chamber that was guarded by a heap of figurines, carved wooden chests and piles of blackened linen. Inside, Youssef and his colleagues found signs that the people buried here had wealth and privilege: gilded masks, a finely carved falcon and a painted scarab beetle rolling the sun across the sky. Yet this was no luxurious family tomb, as might have been expected. Instead, the archaeologists were astonished to discover dozens of expensive coffins jammed together, piled to the ceiling as if in a warehouse. Beautifully painted, human-shaped boxes were stacked roughly on top of heavy limestone sarcophagi. Gilded coffins were packed into niches around the walls. The floor itself was covered in rags and bones.

This eerie chamber is one of several “megatombs,” as the archaeologists describe them, discovered last year at Saqqara, the sprawling necropolis that once served the nearby Egyptian capital of Memphis. The excavators overseen by Youssef uncovered hundreds of coffins, mummies and grave goods, including carved statues and mummified cats, packed into several shafts, all untouched since antiquity. The trove includes many individual works of art, from the gilded portrait mask of a sixth- or seventh-century B.C. noblewoman to a bronze figure of the god Nefertem inlaid with precious gems. The scale of discoveries—captured in the Smithsonian Channel documentary series “Tomb Hunters,” an advance copy of which was made available to me—has excited archaeologists. They say it opens a window into a period late in ancient Egyptian history when Saqqara was at the center of a national revival in pharaonic culture and attracted visitors from across the known world. The site is full of contradictions, entwining past and future, spirituality and economics. It was a hive of ritual and magic that arguably couldn’t seem more distant from our modern world. Yet it nurtured ideas so powerful they still shape our lives today.

* * *

Travelers visiting Egypt have long marveled at the vestiges of the pharaohs’ lost world—the great pyramids, ancient temples and mysterious writings carved into stone. But Egyptology, the formal study of ancient Egyptian civilization, didn’t begin in earnest until Napoleon Bonaparte invaded at the turn of the 19th century and French scholars collected detailed records of ancient sites and scoured the country for antiquities. When Jean-François Champollion deciphered hieroglyphs, in the 1820s, the history of one of humanity’s great civilizations could finally be read, and European scholars and enthusiasts flocked to see not only the pyramids at Giza but also the colossal Ramses II statues carved into the cliffs at Abu Simbel and the royal tombs in Luxor’s Valley of the Kings.

Apart from its eroding pyramids, Saqqara was known, by contrast, for its subterranean caverns, which locals raided for mummies to use as fertilizer and tourists ransacked for souvenirs. Looters carted off not only mummified people but also mummified animals—hawks, ibises, baboons. Saqqara didn’t attract much archaeological attention until the French Egyptologist Auguste Mariette, who became the first director of Egypt’s Antiquities Service, visited in 1850. He declared the site “a spectacle of utter devastation,” with yawning pits and dismantled brick walls where the sand was mixed with mummy wrappings and bones. But he also noticed the half-buried statue of a sphinx, and probing further he found a sphinx-lined avenue leading to a temple called the Serapeum. Beneath the temple were tunnels that held the coffins of Apis bulls, worshiped as incarnations of Ptah and Osiris.

Since then, excavations have revealed a history of burials and cult ceremonies spanning more than 3,000 years, from Egypt’s earliest pharaohs to its dying breaths in the Roman era. Yet Saqqara has remained overshadowed by the glamour of Luxor to the south, where in the second millennium B.C. pharaohs covered the walls of their tombs with depictions of the afterlife, and the Great Pyramids just miles to the north.

It certainly took a while for Mostafa Waziri, the archaeologist directing the latest project, to be converted to Saqqara’s charms. He spent most of his career excavating in Luxor, but in 2017 he was appointed director of Egypt’s Supreme Council of Antiquities (making him, among other things, a successor to Mariette). The new job entailed a move to Cairo. Continuing to dig in southern Egypt was therefore no longer practical, he says, but on his doorstep was another great opportunity: “I realized it was less than one hour from my office to Saqqara!”

Working with an Egyptian team, including Youssef, the site director, Waziri chose to excavate near a mysterious temple called the Bubasteion, dedicated to the cat goddess Bastet, that had been cut into limestone cliffs near the site’s eastern boundary around 600 B.C. A group of French archaeologists had worked nearby for decades, where they found, among other discoveries, the 14th-century B.C. tomb of King Tutankhamen’s wet nurse, Maia. But Waziri targeted an area that the French team had used to pile the debris from their excavations, calculating that whatever lay beneath it had remained untouched.

His approach paid off. In December 2018, Waziri announced the discovery of a 4,400-year-old tomb, intact and ornately carved, that belonged to a high-ranking priest named Wahtye. The next season yielded intriguing caches of animal mummies—not just cats but a cobra, a lion cub, a mongoose and even a scarab beetle. Then, in September 2020, the team unearthed a vertical shaft dug 30 feet down into the bedrock, the first of the “megatombs.” In separate niches at the bottom were two giant coffins, and when the archaeologists cleared the surrounding debris they found dozens more. “I had to call the [antiquities] minister,” says Waziri. “He asked me, ‘How many?’” Eight months later, Waziri is still counting.

* * *

In a simple conservation lab set up at the site, Youssef and his colleagues admired the first coffin to be removed from the shaft. Sealed with black resin, it was roughly human-shaped but huge and squat—more than 7.5 feet long and 3 feet wide—with a wide, impassive face. Removing the intricately carved wooden lid revealed a glint of gold: A second coffin was nested inside, complete with gilded mask. Beautifully preserved, it showed the face of a woman with large, kohl-lined eyes. The rest of the inner coffin was intricately painted in blue, green and red, and included flower and leaf motifs and a depiction of the sky goddess, Nut, with outstretched wings. Most exciting, though, were the hieroglyphs, because they provided valuable information about the occupant: not just spells to aid her journey to the afterlife but details of her family, as well as her name: Ta-Gemi-En-Aset.

These details and the distinctive style of the coffin indicate that she lived during the sixth or seventh century B.C., at the start of Egypt’s Late Period, when a pharaoh named Psamtik I reunified the country after a period of instability and foreign invasions. Egypt was strong and prosperous once again, a global power alongside Babylon and Persia. Psamtik also revived the powerful city of Memphis, then home to around two million people, and nearby Saqqara to hold its dead. According to Campbell Price, curator of Egypt and Sudan at the Manchester Museum in England, the name Ta-Gemi-En-Aset means “she who was found by Isis.” The coffin inscriptions describe her mother as a singer, and include a symbol representing a sistrum, a musical rattle used in temples. Price suggests that Ta-Gemi may have belonged to the cult of Isis, and perhaps played a role in rituals and festivals in a nearby temple devoted to the goddess.

The second coffin retrieved from the shaft was similar to Ta-Gemi’s, and it also contained an inner coffin with a gilded mask. This time, the portrait mask showed a bearded man named Psamtik (probably in honor of one of several pharaohs of this period who shared the name). At first, the team wondered whether Ta-Gemi and Psamtik were related. The hieroglyphs revealed that their fathers had the same name: Horus. But their mothers’ names were different, and further discoveries revealed a different picture.

The team dug deeper, a painfully slow process that involved the help of local laborers, who scooped out the sand by hand and hauled basketsful of debris to the surface using a traditional wooden winch called a tambora, the design of which hasn’t changed in centuries. Below Psamtik’s burial niche was a room filled with many additional coffins, covered in rubble and damaged by ancient rockfalls. The bottom of the shaft led to a second, even bigger cavern, inside of which were jammed more than a hundred coffins of different styles and sizes. There were also loose grave goods, including ushabtis, miniature figures intended as servants in the afterlife, and hundreds of Ptah-Sokar-Osiris statuettes. There were even coffins buried in the base of the shaft itself, as if whoever put them there was running out of space. The result was a megatomb described by the research team as the largest concentration of coffins ever unearthed in Egypt.