Alberta’s Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology says stomach contents have been found preserved inside a fossilized tyrannosaur.

In 2009, when palaeontologists at the museum found a fossil poking out of the ground in the Badlands of Dinosaur Provincial Park, they didn’t know the significance of their discovery.

It took technicians years to painstakingly remove bits of rock from the fossilized bones.

Darla Zelenitsky, an associate professor in dinosaur palaeobiology at the University of Calgary, says the dinosaur turned out to be a well-preserved juvenile Gorgosaurus libratus.

“The specimen itself is about 75.3 million years old,” she said. “And it wasn’t until they brought it back to the museum to clean it up that they had found that there were prey items preserved inside the stomach.”

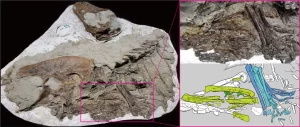

While technicians were cleaning the specimen, they noticed small toe bones poking out of the rib cage from the animal’s gut. Zelenitsky says the challenge was to determine what those bones belonged to.

“We were able to take bones from the drawers of the museum and directly compare them to figure out exactly what species this dinosaur was,” she said. “It turned out to be a small bird-like dinosaur called Citipes (elegans), and it’s actually two individuals that are preserved in the stomach of this tyrannosaur.”

Francois Therrien, the curator of dinosaur palaeoecology at the museum, says it’s a one-in-a-billion find.

Young Gorgosaurus skeletons are extremely rare because the bones are fragile and are rarely preserved and fossilized.

“To preserve stomach contents, you really need a unique sequence of events. First, your specimen needs to have eaten something just before it died, because we know these animals digested their food really, really fast,” he said.

“Then, it had to be buried under sediment really quickly, because otherwise scavengers will come and eat the carcass.”

Curator of Dinosaur Palaeoecology at the Royal Tyrrell Museum Dr. Francois Therrien, right, and University of Calgary assistant professor Dr. Darla Zelenitsky stand next to a young specimen of a dinosaur called Gorgosaurus libratus in an undated handout photo. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Royal Tyrrell Museum of Palaeontology)Therrien says this dinosaur ate just the meaty legs of two Citipes, and those fossils are rare in themselves.

“It’s only known from a handful of feet,” he said. “Now we have entire legs so those are actually the most complete skeletons of Citipes ever discovered, because they were swallowed by a Tyrannosaur.”

The findings and subsequent study conducted by an international team lead by Therrien and Zelenitsky are published in the journal Science Advances.

“We knew right away this was a very unusual and unique find,” said Zelenitsky. “So to me, it’s a huge deal, it’s a once in a career type of a fossil.”

The discovery is telling palaeontologists more about the lifecycle of Gorgosaurus that lived in Dinosaur Provincial Park earlier and in a much different ecosystem from Tyrannosaurus Rex.

“The oldest known Tyrannosaur in terms of biological age is 21 or 22-years-old, and they were preying on mega herbivores,” said Zelenitsky. “So large horned dinosaurs and duck-billed dinosaurs and we know that from tooth damaged bone (on fossils of their prey).

Therrien says the juveniles from five to ten-years-old fed on much different animals, and because of that, young tyrannosaurs were capable of occupying different ecological niches throughout their lives and that was likely the key to their success as top predators.

“Their hunting strategy is actually totally different from that we see in adults,” he said. “They went for the meatiest parts, they pulled out the drum sticks and then basically they ate the legs and left the rest of the carcass out. Whereas, adults are more like indiscriminate feeders, they’ll just eat anything, crunched bones and swallow everything whole, so we see that they are really different feeding strategies.”

“What we have now is the first solid evidence that tyrannosaurs actually changed their diet through growth,” said Zelenitzky. “From this size of a juvenile which is 350 kilograms to the adults which were 2,000 or more so it’s a really exciting find.”

The specimen will remain behind closed doors in the technical working area of the museum and continue to be studied to determine more about the Gorgosaurus and Citipes fossils and may eventually be put on display in the public gallery.