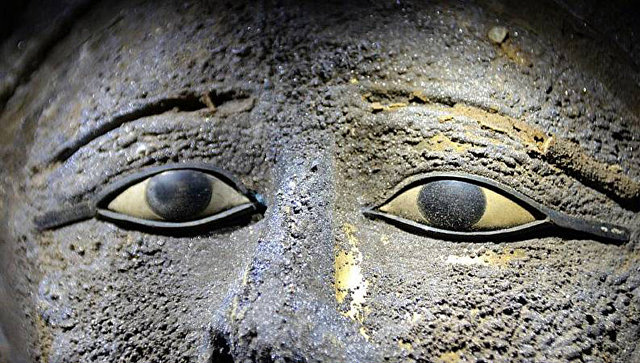

Ancient Egyptian embalmers used at least three different recipes to mummify the head.(Supplied: Nikola Nevenov)

The recipe is based on the analysis of traces of ingredients found on funerary pots excavated from an ancient embalming workshop at Saqqara near the pyramid of King Unas south of Cairo.

Each pot was inscribed with specific instructions on how to use the ingredients such as “put on the head” or “bandage or embalm with it”.

The workshop was found near the pyramid of King Unas in the Saqqara necropolis of Memphis, the first capital of ancient Egypt.(Supplied: Saqqara Saite Tombs Project, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. Photographer S. Beck)

Along with uncovering the secret recipes, the analysis revealed how the use of exotic ingredients in the business of death drove trade networks from as far away as South-East Asia.

“The embalming of the dead shaped the connectivity of the living,” Professor Stockhammer said.

Ancient workshop a window to the past

The workshop in the UNESCO World Heritage listed Saqqara site was discovered in 2016 by study co-author, the late Egyptian archaeologist Ramadan Hussein.

“This was the first embalmers workshop ever found,” Professor Stockhammer said.

The workshop was testament to the industrial nature of the funeral industry that serviced the upper echelons of Egyptian society between 664 BC and 525 BC.

Along with gilded silver masks, mummies and sarcophagi were the remains of mud brick structures and hundreds of ceramics used in the embalming process.

A gilded mask from one of the bodies suggests the workshop was used to prepare Egyptians from the upper society, such as priests, for the afterlife.(AP: Amr Nabil)

On the top level was the embalmer’s workroom or “ibu”, where organs were removed and the body placed in a salt solution for up to 70 days to suck out all the moisture.

Then the body was washed and dropped down a 13-metre shaft into the subterranean embalming room or “wabet”, where it was slathered with substances mixed in the carefully labelled pots.

The labels were crucial to ensure the ritual, which was often supervised by priests, was followed to the letter.

“If you didn’t do it correctly, the eternal existence [of the corpse] was in danger,” Professor Stockhammer said.

Once anointed, the mummies were dropped down another 30m shaft where they were buried, depending on their finances, in single or communal chambers.

The Egyptian mummification workshop at Saqqara was a large structure that contained subterranean embalming room and burial chambers.(Supplied: M. Lang, Universität Bonn)

Karin Sowada, director of the Australian Centre for Egyptology at Macquarie University, said the workshop filled a missing piece in our understanding of Egyptian mummification.

“We have whole scenes, we have texts, we have the mummified bodies from which we can draw information, but the missing piece of this puzzle has always been the embalming workshop,” said Dr Sowada, who was not involved in the research.

“To see the whole package with the workshop, to be able to analyse the chemicals in situ and to see the instructions given is unique.”

Decoding the secret recipes of ancient embalmers

To understand what substances were used, Maxime Rageot of the University of Tübingen, Germany worked with colleagues at the National Research Centre in Egypt to analyse 31 of the 121 bowls and beakers excavated from the site.

Using a technique known as gas chromatography mixed with mass spectrometry they were able to identify specific molecules that had seeped into each vessel.

Archaeologists excavated 121 vessels that had been discarded at the Saqqara mummification workshop.(Supplied: Saqqara Saite Tombs Project, University of Tübingen, Tübingen, Germany. Photographer: M. Abdelghaffar)

The technique involves drilling small amounts of material out of the inside of the vessels, so permission is needed to use it on ancient artefacts.

But it is good for analysing fatty acids, said Paul Haynes of Macquarie University, a chemist who specialises in bioarchaeological analysis.

“Fatty acids are great for [looking at] embalming because they’ve got all these oils and resins,” said Professor Haynes, who was not involved in the research.

“You can break down what is in it, and where it comes from.”

The analysis revealed embalmers at Saqqara had at least three different recipes for the head, as well as a number of concoctions to preserve the liver and stomach, apply to bandages, and reduce the stench of death.

In addition, two sacred unguents known as antiu and sefert, mentioned in many ancient texts, were not what researchers previously thought they were.

“Antiu is a substance that Egyptologists have translated as myrrh or frankincense, and now we see its a mixture of oils,” Professor Stockhammer said.

“I don’t want to say that our translation for antui at this workshop is true for all Egyptian times, and all Egyptian contexts … but it shows us we need to rethink these substances.”