The narrative of the saints buried in the catacombs of Northern Europe is an odd one. It stems from the crisis of faith following the Protestant Reformation, which prompted a major return to ornamental materialism in the practice of worship.

In 1578, jewel-encrusted bones were unearthed in catacombs under Rome and offered as replacements to churches that had lost their saint relics during the Protestant Reformation. Nonetheless, their identities remained mostly unknown.

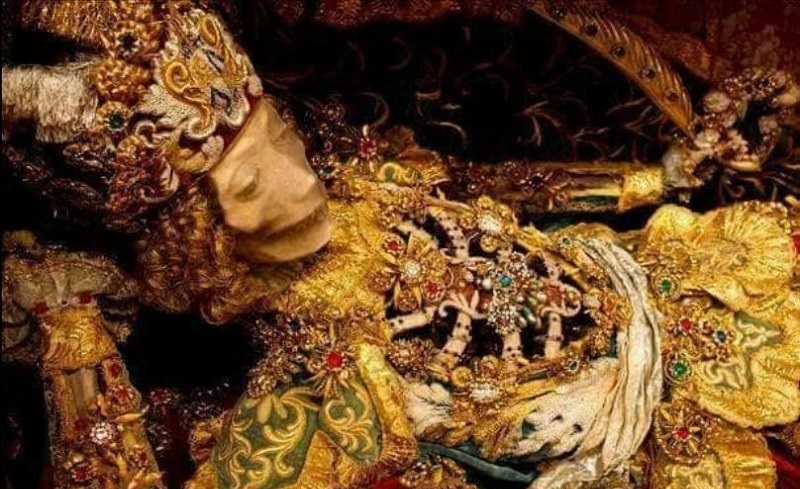

The receiving churches lavished jewels and gold garments on the revered skeleton strangers for years, sometimes even filling their eye sockets and adorning their teeth with finery.

But, when the Age of Enlightenment arrived, they were embarrassing due to the immense wealth and luxury they represented, and many were concealed or removed.

On May 31, 1578, vineyard workers in Rome uncovered a passageway that led to a vast network of long-forgotten catacombs beneath Via Salaria. The Coemeterium Jordanorum (Jordanian Cemetery) and the accompanying catacombs were early Christian burial sites dating back to the first through fifth century A.D.

When these catacombs were found, the Catholic Church had been combating the Reformation for decades. Protestant Reformers saw the retention of relics as idolatry, despite the fact that certain human remains had been venerated as sacred relics for millennia. Even the bodies of saints were to disintegrate into dust. During the Reformation, many relics were buried, disfigured, or destroyed.

The Counter-Reformation employed the transfer of new holy relics into German-speaking countries as a tactic. Relics have long been a popular item among the laity. Where would they find new saints to replace those who had been lost?

Prior to the discovery of these catacombs, the Catholic Church had been resisting the Reformation for decades. Despite the fact that specific human remains had been treasured as holy relics for centuries, Protestant Reformers considered the retention of relics to be idolatry. Bodies, even the bodies of saints, were to decay into dust. Throughout the Reformation, several relics were buried, disfigured, or destroyed.

The Counter-Reformation employed the transportation of new holy relics into German-speaking nations as a tactic, given the laity’s long-standing fascination with relics. They needed to replace what had been lost, but where could they locate additional saints?

They were undeniably emblems of grandeur. From the skull to the metatarsal, the skeletons were decked in gold and jewels and given Latin names. The ornamentation varied, but was often rich. The skeletons wore velvet and silk robes embroidered with gold thread, and the gems were either authentic or expensive replicas. Even silver-plated armor was only made available to a chosen few.

In 1676, Saint Coronatus entered a monastery in Heiligkreuztal, Germany Shaylyn Esposito

With the time, money, and effort necessary to construct the saints, it is disheartening to consider how few have survived to the present day. As they were considered morbid and degrading, many were stripped of their gems and buried or destroyed during the nineteenth century.

Just around five percent of the catacomb saints who once populated Europe survive, and few may be examined by the public.