In the 1995 post-apocalyptic action film “Waterworld,” the polar ice caps have completely melted and the water level has risen to over 5 miles, engulfing nearly all of the land.

Unlike any other planet in our solar system, astronomers have identified two actual “water worlds.”

They are slightly larger than the planet Earth, but lack the rigidity of rock. Despite this, they are denser than the gas-giant gas-giant planets that orbit the Sun. Then, what do they consist of? The most plausible explanation is that the oceans on these exoplanets are at least 500 times deeper than those on Earth, which are only a wet surface on a rocky ball.

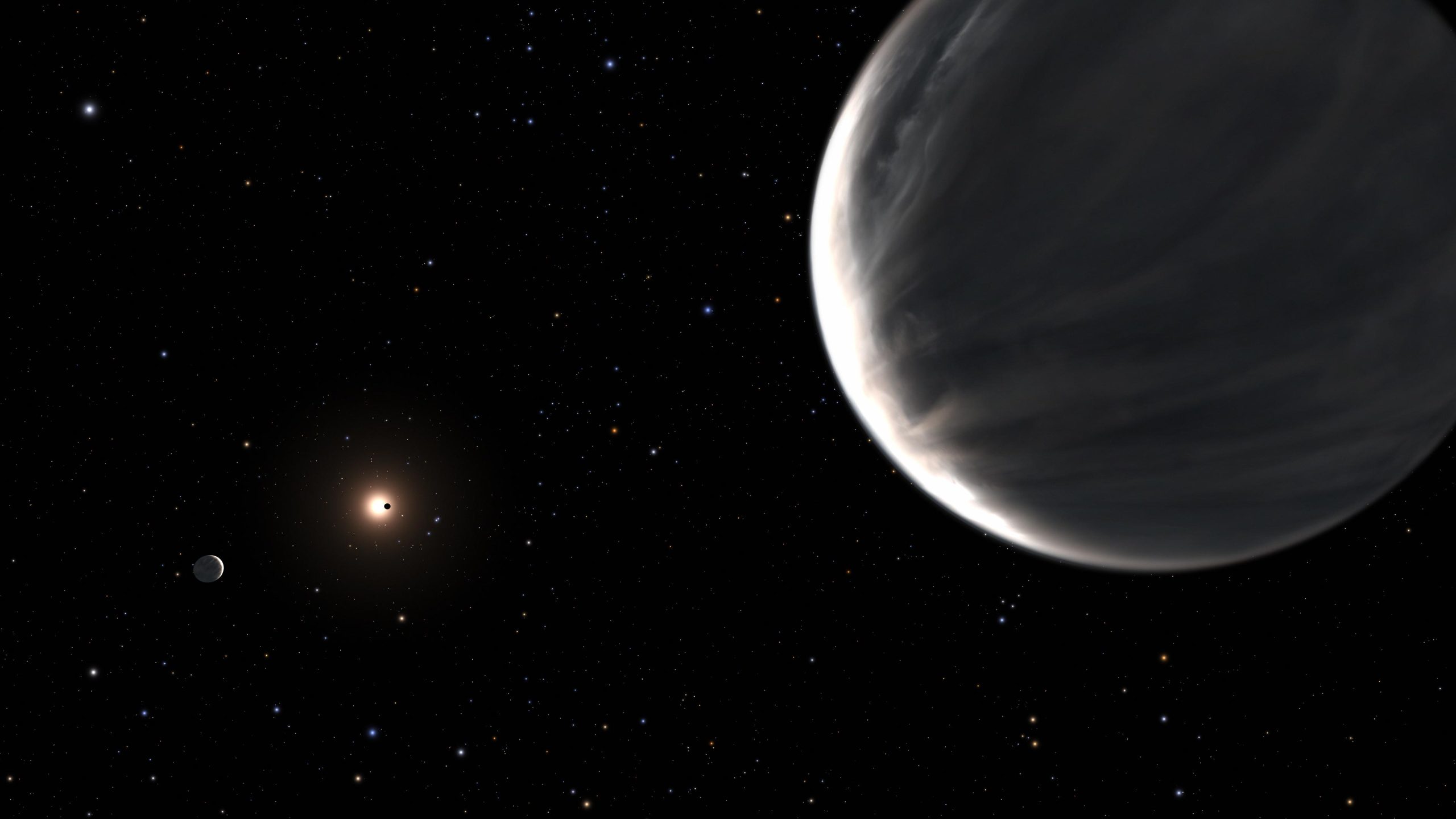

The wet planets orbit the red dwarf star Kepler-138, which is located 218 light-years away in the constellation Lyra at a distance of 218 light-years. The planets were discovered in 2014 owing to NASA’s Kepler Space Observatory.

According to subsequent measurements with the Hubble and Spitzer satellite observatories, the planets must be composed primarily of water. It was not possible to view water’s spectral signature directly. Nevertheless, their density, which is calculated by comparing their mass and size, led to this outcome.

Do not look for fish in the world’s waterways. Since both the ocean surface and the atmosphere are extremely warm and pressurized, it seems unlikely that there is a distinct separation between the two.

Astronomers have discovered evidence that two exoplanets orbiting a star 218 light-years away are “water worlds” in which water comprises a major amount of the planet’s mass. This evidence was found utilizing data from the Hubble and Spitzer Space Telescopes operated by NASA. Paul Morris, Principal Producer, Goddard Space Flight Center, NASA

Despite the inability of telescopes to directly inspect their surfaces, the planets’ densities indicate that they are heavier than gas-dominated planets but lighter than rock-dominated planets.

Two exoplanets orbiting a red dwarf star have been identified as “water worlds,” where water constitutes a large amount of the planet’s mass, according to data collected by a team of scientists led by the University of Montreal. These planets are located in a planetary system 218 light-years away in the constellation Lyra and are unlike any planet in our solar system.

The scientists, lead by Caroline Piaulet of the Trottier Institute for Research on Exoplanets (iREx) at the University of Montreal, published a comprehensive investigation of this planetary system, also known as Kepler-138, in the journal Nature Astronomy on December 15.

Kepler-138 c and d may be composed primarily of water, according to study conducted by Piaulet and colleagues utilizing NASA’s Hubble and defunct Spitzer satellite observatories. These two planets and Kepler-138 b, a smaller companion planet located closer to the star, have been discovered by NASA’s Kepler Space Telescope. Additionally, the most recent analysis uncovered evidence of a fourth planet.

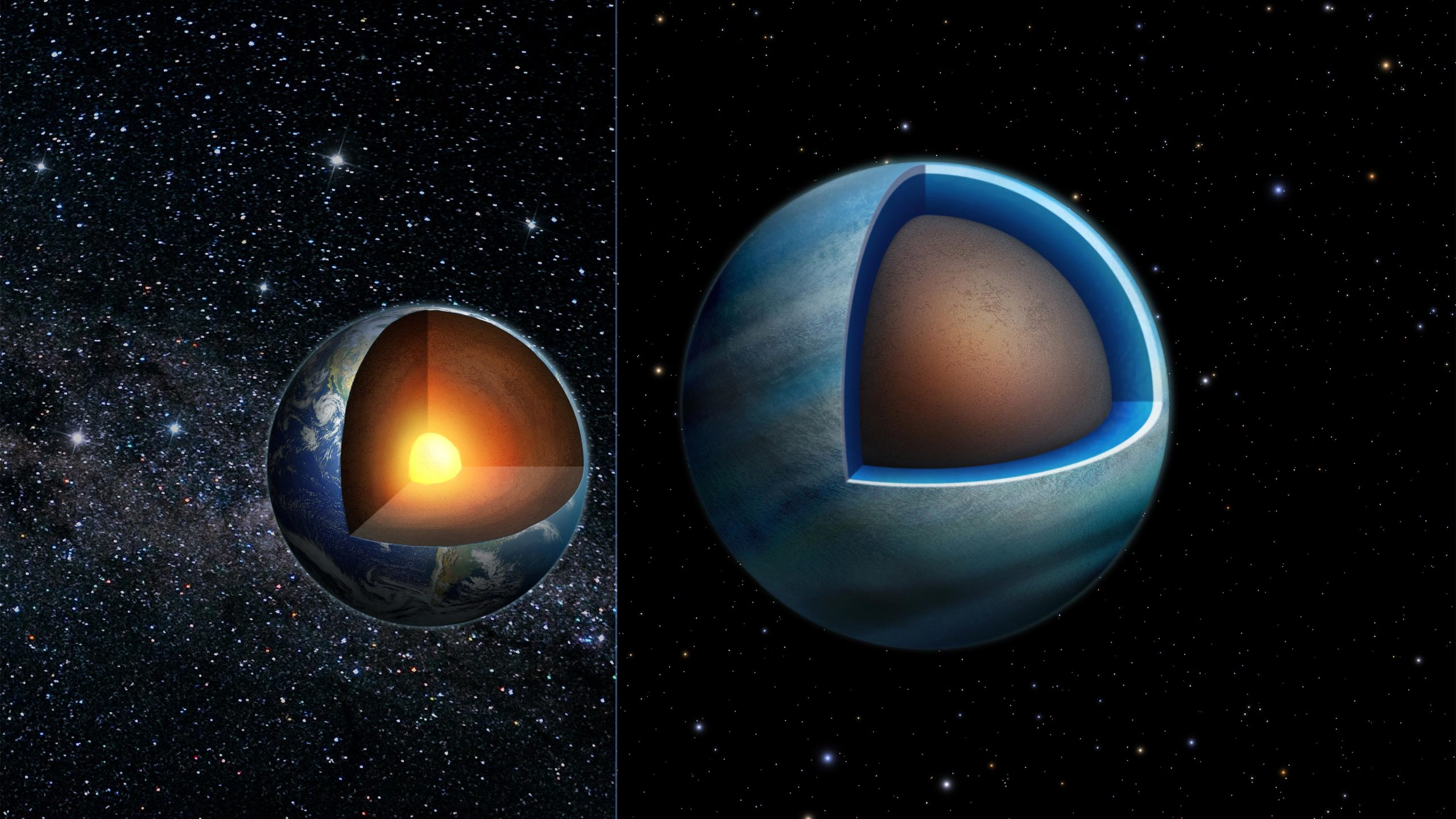

This image shows Super-Earth Kepler-138 d in the foreground. On the left is the planet Kepler-138 c, while Kepler-138 b is visible in shadow transiting its star in the background. The distance to the red dwarf star Kepler 138 is 218 light-years. Due to their low density, Kepler-138 c and d, which are nearly identical in size, must be composed primarily of water. They cannot both be solid rocks, as they are almost twice as large as the Earth yet only half as dense. Based on estimations of their mass in relation to their physical diameter, they differ from all other major planets in our solar system and are considered a new type of “water planet.” Kepler-138 b, one of the smallest known exoplanets, with the mass and density of Mars. Leah Hustak, NASA, and ESA (STScI)

By comparing the planets’ diameters and masses to models, astronomers have concluded that up to half of Kepler-138 c and d’s composition should consist of material heavier than hydrogen or helium but lighter than rock (which constitute the bulk of gas giant planets like Jupiter). The most abundant of these possible components is water.

Bjorn Benneke, co-author of the study and professor of astrophysics at the University of Montreal, stated, “We previously believed that planets that were a little larger than Earth were massive spheres of metal and rock, similar to enlarged versions of Earth.

Therefore, we referred to them as “super-Earths.”

However, we have now demonstrated that the nature of these two planets, Kepler-138 c and d, is markedly different from one another and that a large fraction of their total volume consists of water. The existence of water worlds, a type of planet long predicted by astronomers, is now backed by the greatest evidence to date.

Planets c and d have significantly lower densities than Earth despite having volumes and masses that are more than three times as vast as those of Earth.

This is unexpected given that the vast majority of planets that are only slightly larger than Earth that have been properly studied to date appeared to be identical to our own rocky planet. According to specialists, the closest analogs would be many icy moons in the outer solar system that have a rocky core and are primarily composed of water.

Piaulet stated, “Consider enlarging Europa and Enceladus, the water-rich moons that orbit Jupiter and Saturn, and bringing them far closer to their star. They would host massive water vapor envelopes instead of ice.

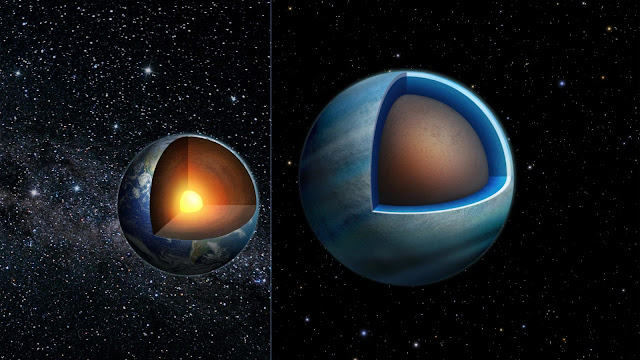

Cross-sectional artist’s rendering of the Earth (left) with the exoplanet Kepler-138 d (right). On Kepler-138 d, a substantial layer of high-pressure water exists in multiple forms, including supercritical and perhaps liquid water deep within the planet and an extensive water vapor envelope (various hues of blue) above it. This exoplanet, like Earth, contains an interior composed of metals and rocks (brown portion). More than fifty percent of its volume, or 1,243 miles, consists of these water strata (2,000 kilometers). In contrast, the oceans on Earth average less than 2.5 miles in depth and contain a negligible amount of liquid water (4 kilometers). Benoit Gougeon of the University of Montreal deserves credit.

According to researchers, the planet’s surface waters may not be similar to those on Earth. Since the atmosphere of Kepler-138 d is most likely above the boiling point of water, we predict a thick, dense atmosphere composed of steam. According to Piaulet, high-pressure liquid water or water in another phase that occurs at high pressures and is known as a supercritical fluid could only exist in a steam environment.

In 2014, astronomers announced the finding of three planets around Kepler-138 using Kepler Space Telescope data. This was based on the theory that the planet temporarily passed in front of its star, causing a dramatic dimming.

Diana Dragomir and Benneke of the University of New Mexico proposed re-observing the planetary system between 2014 and 2016 using the Hubble and Spitzer space telescopes to investigate the atmosphere of Kepler-138 d, the third planet in the system, more precisely.

Two prospective water planets, Kepler-138 c and d, are not located in the habitable zone, which is the region surrounding a star where temperatures allows liquid water to exist on a rocky planet’s surface. In addition, scientists identified evidence of a brand-new planet, Kepler-138 e, in the habitable zone using Hubble and Spitzer data.

This newly discovered planet has a 38-day orbital period, is smaller than the other three, and is located further from its star. Due to the fact that this additional planet does not appear to transit its host star, its nature remains unknown. Astronomers may have determined the size of the exoplanet by studying its transit.

Using the transit timing-variation approach, the masses of the previously discovered planets were recalculated in light of Kepler-138 e. This method entails observing minute variations in the precise timing of a planet’s transit in front of its star, caused by the gravitational attraction of other surrounding planets.

Contrary to what was previously believed, the two water planets Kepler-138 c and d are in fact “twin” planets that are nearly equal in size and mass. In contrast, Kepler-138 b, the planet that is closer to Earth, is confirmed to be a Mars-mass planet and one of the smallest exoplanets identified to date.

“As our instruments and methods get more sensitive to identify and analyze planets that are further from their stars, we may begin to find a great deal more of these water-rich worlds,” Benneke said.