What every exciting tale from history needs is a daring and boisterous hero. Götz von Berlichingen is exactly the type of a historical figure that embodied all the features of a leader that was destined for greatness. A defiant and powerful German noble, Götz led a life filled with excitement and defining events. He was involved in numerous feuds and was renowned as one of the first men to wear an efficient metal prosthesis. In the Swabian Württemberg region, where he was born, this man is remembered as a folk hero and a central figure of many entertaining and inspiring tales. And all that because he was a defiant knight that lived life based on his own rules!

A copper engraving portrait of Götz von Berlichingen, City Museum of Cologne.

Götz von Berlichingen’s Life As an Aristocratic 10th Child

The Berlichingens were a noble, aristocratic family from the eponymous town of the modern-day Baden-Württemberg region in Germany’s medieval period. In 1480, Gottfried von Berlichingen was born into this great family, although no one suspected just how famous he would become. Gottfried was the name given to him, but it was rarely used. Throughout his life he was known simply as Götz.

His noble parents, Lord Kilian von Berlichingen and Margaretha von Thüngen, raised their son at the idyllic Jagsthausen Castle, which was the ancestral seat of their family. However, Götz was the tenth child, and had slim chances to become an heir of the family’s noble title. So, like many of the lesser sons of the time, he devoted his life fully to military pursuits.

When he was a child, he was sent to the monastery school at Niedernhall, but it quickly became obvious that the boy was too headstrong and willful to lead a life of courtly rules and leisure. So, his father sent him to a seasoned soldier and commander, the noble Veit von Lentersheim, where Götz began his soldierly training.

In 1497, when Götz von Berlichingen was about seventeen years old, he entered the service of a powerful margrave, Frederick I, of Brandenburg-Ansbach, beginning his career as a free knight. A free knight was in simplest terms a mercenary, freely entering the service of various feuding sides for personal profit.

While in the retinue of Frederick I, Götz fought in the armies of the Holy Roman Empire and its Emperor, Maximilian I. This employment led him to many battlefields across Europe: Brabant, Burgundy, Lorraine, and the bloody Swabian War. In these conflicts he excelled as a capable leader and a headstrong, skilled warrior.

In the year 1500, when he was just 20 (and already a veteran of many battles), Götz von Berlichingen left the service of Frederick I, and set out on his own. In that same year he formed his own company of mercenary knights, and began selling his military services to any baron, margrave, or duke that required them.

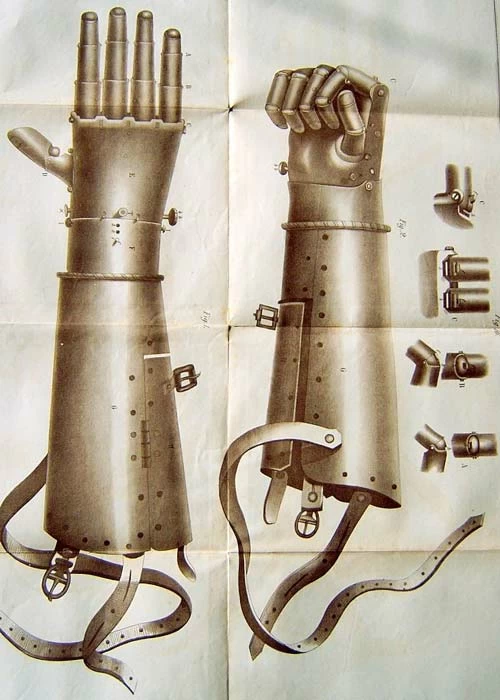

An old drawing of the second iron prosthetic hand worn by Götz von Berlichingen. (Public domain)

Sword for Hire: How Götz von Berlichingen Lost his Arm

Early in their independent mercenary career, Götz and his knights entered the service of the Bavarian Duke Albert IV, fighting to resolve his feuds. In 1504, Götz was besieging the city of Landshut for the Bavarian Duke, where one of the greatest misfortunes of his life occurred. During the siege, the enemies fired a cannon ball that hit Götz’s sword and forced the blade to cut into his arm. The blade bit deep at his elbow, and the battlefield surgeons had to quickly amputate his lower arm. For an exceptionally skilled knight to lose a hand at just 24 years of age was nothing short of a disaster. Usually, such an injury meant a man’s fighting days were over. But Götz didn’t see it this way at all!

Götz von Berlichingen chose to think out of the box. He had a local craftsman create an elaborate iron hand for him. It was not a simple and crude replacement: it was a mechanical iron prosthesis that allowed him to retain some effective use of his arm. Still, his first iron hand was somewhat crude, and a number of years later, Götz had another one made.

The second prosthesis was more elaborate and much larger. For the period, it was a true wonder: it implemented a complex design that used springs and allowed for the segmented movement of fingers. Götz was thus able to hold a quill, a shield, reins, and to use his hand more efficiently. From that point on, he became known as the knight with the iron hand, or Götz von Berlichingen mit der eisernen Hand. Both of these prosthetic arms are now on display at the family’s ancestral seat at the Jagsthausen Castle.

The original armor worn by Götz von Berlichingen, on exhibit in the Hornberg museum at Hornberg Castle where he died at the ripe age of 82.

With His Iron Hand Götz Continued His Mercenary Work

With his new iron hand, Götz continued his daring exploits and deeds. His mercenary career went on as before, as did his numerous feuds. During his life, Götz was involved in around 15 feuds in just his own name. On most occasions, he feuded with entire cities, rather than individuals. These included Ulm, Cologne, Augsburg, and Nuremberg. He was also involved in many more feuds that were not his own. In those cases, he lent his aid to his many friends.

In 1512, Götz received his first Imperial ban. This was a punishment directly from the Emperor, which in essence decried Götz as an outlaw, and allowed anyone to kill him freely and without repercussions. He was placed under this ban due to his actions against the city of Nuremberg. Götz had a long-standing feud with this city. So, he raided a group of wealthy merchants from Nuremberg while they were returning from a fair. This resulted in the ban.

It was only two years later, in 1514, that he overcame the ban by paying a hefty fine of 14,000 guilders. And thus, Götz was able to continue with his feuds and battles. In 1516, he raided Hesse because of his personal feud with Mainz and its Archbishop-Elector. During this raid he kidnapped Count Phillip IV of Waldeck and held him for ransom. After the Count was ransomed, Götz was charged with a second Imperial ban.

Götz von Berlichingen is perhaps best remembered for one of his witty catchphrases. In 1516, during the above-mentioned feud with Mainz, he was laying siege to a castle, attempting to lure the bailiff out on the ramparts. When the bailiff finally appeared, Götz famously said to him after an altercation: “Er solte mich hinden lecken!” or “Er kann mich im Arsche lecken!” Both phrases can be translated to “He can kiss my ass!” Saying this, he defiantly rode away. The phrases remained as an iconic symbol of his willful defiance and became known as the “Swabian greeting.” Today it is used throughout Germany as a witty and light comeback.

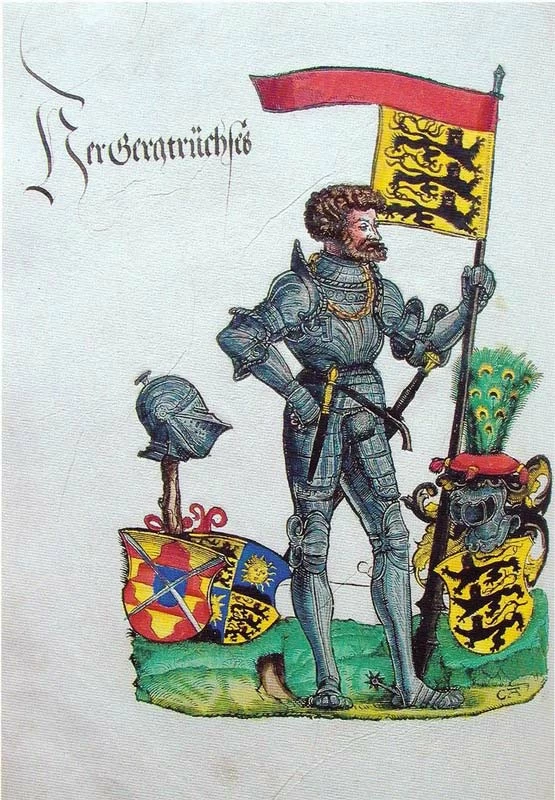

Bauernjörg, Georg, Truchsess von Waldburg, the Scourge of the Peasants and leader of the Swabian League and therefore also the enemy of Götz, who sided with the peasants in a half-hearted way near the end of his fighting life. (Christoph Amberger / Public domain)

Götz Loses Against Swabian League and Fights for Peasants

By 1519, Götz was once more in service as a mercenary knight. He fought for Ulrich, the Duke of Württemberg, against the powerful Swabian League. During this conflict, Götz was besieged in the town of Möckmühl, where he experienced defeat: he was forced to surrender the town due to running low on supplies and ammunition. He was captured and imprisoned, but successfully freed in 1522, after his fellow knights raised a sum of 2,000 guilders to buy his freedom.

In 1524, the German Peasants War erupted. This was a large-scale revolt by the realm’s lower classes, who were rebelling due to their harsh economic situation. Götz von Berlichingen joined on the side of the peasants and led one of their rebel armies in the region of Odenwald. Contrary to popular belief, he didn’t do this for a noble cause or for his disdain of the Imperial authority. He himself stated that he did so because he had little choice, and that he didn’t support the peasants’ original cause.

He didn’t lead the peasant army in a real serious and dedicated way. After failing to control the peasants and exert his influence, he left his command post and returned to his seat of Jagsthausen without being involved in the action. The peasant rebellion, of course, failed with high casualties in 1525.

Soon after the peasant defeat, Götz was called before the Diet of Speyer, where he was to answer for his actions against the Empire. Luckily, he was acquitted in 1526.

Still, old grudges die hard. Having feuded for most of his life, Götz had plenty of enemies. The foremost of these was the Swabian League. In 1528, he was invited into the city of Augsburg and promised safe passage and a chance to rid himself of all the charges that the League raised against him. This was, however, an elaborate ruse, and Götz von Berlichingen fell for it. He was captured and imprisoned until 1530. He was freed from captivity in that year, after swearing that he wouldn’t attack the Swabian League again, and that he would return to his castle at Hornberg and remain there.

A plaque of Götz with his famous quote: “But he, tell him, he can lick my arse,” from Goethe’s play on display in a street in Weisenheim am Sand, southwest Germany. (Immanuel Giel / Public domain)

Götz Immortalized in Goethe’s Play With Same Name

Götz stayed true to his word. He stayed in the region near his castle, and was largely dormant until 1540, when he was at long last released from his second Imperial ban by Emperor Charles V. The Emperor did this likely for his own gains, as he needed a leader as experienced as Götz of the Iron Hand, in order to face the threat of the Ottoman Empire. Götz agreed to serve the Emperor against them in his 1542 campaign in Hungary, even though he was around 62 years old at the time. Two years later he was also involved in the Imperial invasion of France.

Following these actions, Götz von Berlichingen entered his much-deserved retirement. He returned to his castle at Hornberg, remaining there until his death on July 23rd, 1562. He was around 82 at the time. He left behind 10 children from two marriages.

Götz von Berlichingen wrote an extensive autobiography in his lifetime, which was published only in 1731, long after his death. It was published in a time of German national re-awakening, and quickly became popular, placing Götz once more to the legendary status he had during his life. The autobiography caught the attention of the widely celebrated German author, Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, who used it as a basis for his 1773 play, “Götz von Berlichingen.”

The play was an instant hit in theaters across Germany. It made Götz an even more popular folk hero, as it romanticized his life – making him a Robin Hood-like character who defied authority and helped the oppressed peasants. Goethe didn’t fail to include the most famous of Berlichingen’s quotes:

Götz von Berlichingen (when commanded to surrender)

“Surrender! Throw myself on his mercy! Who are you talking to?! Am I a robber?! Tell your captain: For His Imperial Majesty, as ever, I have all due respect. As for him, however, tell him he can lick me in the ass!”

Hornberg Castle was for decades Götz von Berlichingen’s home and base between feuds and mercenary work. He died here in 1562.

Götz von Berlichingen: Germany’s Stubborn Robin Hood

Goethe’s play immortalized Berlichingen’s quote and his consistently boisterous and willful character. It served as a major inspiration throughout the following centuries, especially at a time when the German people needed strong folk heroes from their past.

And even today, we can all learn plenty of major lessons from the life and deeds of Götz von Berlichingen. We can understand that bravery, honor, and perseverance almost always pay off, and that one has to stick to one’s true cause. Götz was a unique character, without a doubt. A warrior, a poet, and daring hero, his life was truly filled to the brim. And he chose never to give up: even after losing an arm!

Top image: Close up of a medieval knight’s steel armor and his sword hilt bursting with flames of fire held by an iron hand. Germany’s knight, mercenary fold hero, Götz von Berlichingen, was a man that defines the power of this knight image: perseverance, bravery, and strength.