They were the largest animals to ever walk the Earth: sauropods, a dinosaur clade of such immense size and stature, they’re sometimes dubbed ‘thunder lizards’.

These towering hulks – including Brontosaurus, Brachiosaurus, and Diplodocus among others – needed four thick, powerful legs to support and transport their massive bodies. At least, most of the time. Perhaps.

Some mysterious, ancient tracks described in a new study could offer fresh support for a disputed view in palaeontology: that these lumbering giants sometimes got around on two legs, not four, belying what their quadruped status (and simple physics) would seem to demand.

As strange as it might sound, this hypothesis dates back several decades, to when fossil researcher Roland T. Bird identified some unusual dinosaur tracks laid down on ranch grounds in the county of Bandera, Texas.

What made the tracks unusual was that the marks were manus only, referring to footprint impressions made by front limbs, not the rear limbs (known as pes).

“Without a doubt made by a sauropod, but as I interpret them, made by an individual while swimming,” Bird wrote in a letter in 1940.

“They were all typical forefeet impressions as if the animal had just been barely kicking bottom.”

With time, Bird’s interpretation of these manus-only tracks fell out of favour, as modern palaeontology came to realise that sauropods were primarily land animals, not aquatic as was once thought.

The alternative view to explain manus-only tracks like this is that the forefeet of sauropods (supporting more of the animals’ body weight) are all that leaves track marks on certain kinds of ground surfaces, as the rear limbs, supporting less weight, leave less impression on soil and sediment.

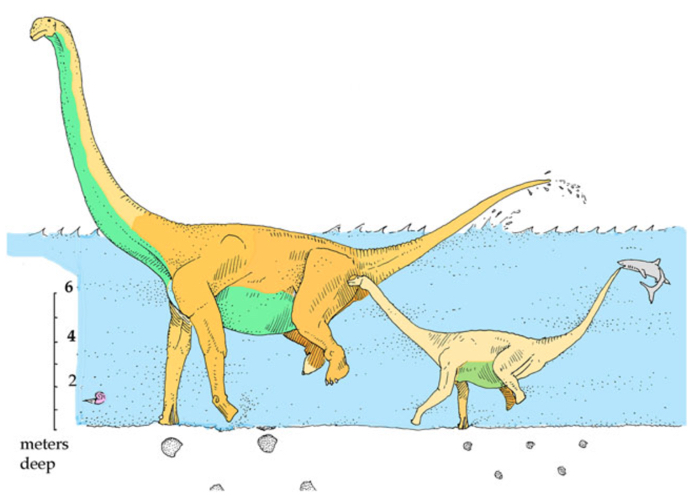

While that might now be the generally preferred interpretation of manus-only sauropod tracks, the case for dinosaurs treading through shallow, shoulder-height bodies of water on their front limbs (with their rear limbs not reaching the ground) has never been definitively ruled out.

Now, a series of more recently discovered sauropod tracks in Texas gives palaeontologists a chance to reconsider the merits of the arguments.