The 3,400-year-old royal city was built by Amenhotep III, abandoned by his heretic son, Akhenaten, and contains stunningly preserved remains.

Three thousand four hundred years ago, a contentious ancient Egyptian king abandoned his name, his religion, and his capital in Thebes (modern Luxor). Archaeologists know what happened next: The pharaoh Akhenaten built the short-lived city of Akhetaten, where he ruled alongside his wife, Nefertiti and worshipped the sun. After his death, his young son Tutankhamun became ruler of Egypt—and turned his back on his father’s controversial legacy.

But why did Akhenaten abandon Thebes, which had been the capital of ancient Egypt for more than 150 years? Answers may lie in the discovery of an industrial royal metropolis within Thebes that Akhenaten inherited from his father, Amenhotep III. The find, which has been dubbed the “lost golden city of Luxor” in an announcement released today, will generate as much enthusiasm, speculation, and controversy as the renegade pharaoh who left it.

Akhenaten, who left the ‘golden city’ for a new capital at Amarna, encouraged a startlingly different style of Egyptian art. Here he is shown with his wife, Nefertiti, and three daughters.

Photograph by Universal History Archive/Getty

Because the city was initially discovered just in September of last year, archaeologists have only scratched the surface of the sprawling site, and understanding where this discovery ranks in Egyptological importance is hard to say at this time. The level of preservation found so far, however, has impressed researchers.

“There’s no doubt about it; it really is a phenomenal find,” says Salima Ikram, an archaeologist who leads the American University in Cairo’s Egyptology unit. “It’s very much a snapshot in time—an Egyptian version of Pompeii.”

The site dates from the era of 18th-dynasty pharaoh Amenhotep III, who ruled between around 1386 and 1353 B.C. and presided over an era of extraordinary wealth, power and luxury. In Amenhotep III’s final years, he is thought to have briefly reigned alongside his son, Akhenaten.

But a few years after his father’s death, Akhenaten, who ruled from around 1353–1336, broke with everything the late ruler stood for. During his 17-year reign, he upended Egyptian culture, abandoning all of the traditional Egyptian pantheon but one, the sun god Aten. He even changed his name from Amenhotep IV to Akhenaten, which means “devoted to Aten.”

The heretic pharaoh didn’t stop there. Akhenaten moved his royal seat from Thebes north to a completely new city he called Akhetaten (modern site name: Amarna) and oversaw an artistic revolution that briefly transformed Egyptian art from stiff and uniform to animated and detailed. But after his death, most traces of the ruler were obliterated. Starting with his son, the boy king Tutankhamun, Akhenaten’s capital, his art, his religion, and even his name was dismissed and systematically wiped from history. Only the rediscovery of Amarna in the 18th century revived the legacy of the renegade leader, which has fueled archaeological speculation for hundreds of years.

Why and how did the pharaoh’s controversial transformation take place, and what was everyday life like under the great Amenhotep III? The newly found city could provide clues. The excavation site straddles old and new in an area renowned for its archaeological riches. To the north is Amenhotep III’s 14th-century B.C. mortuary temple, and to the south is Medinet Habu, a mortuary temple built almost two centuries later for Ramses III.

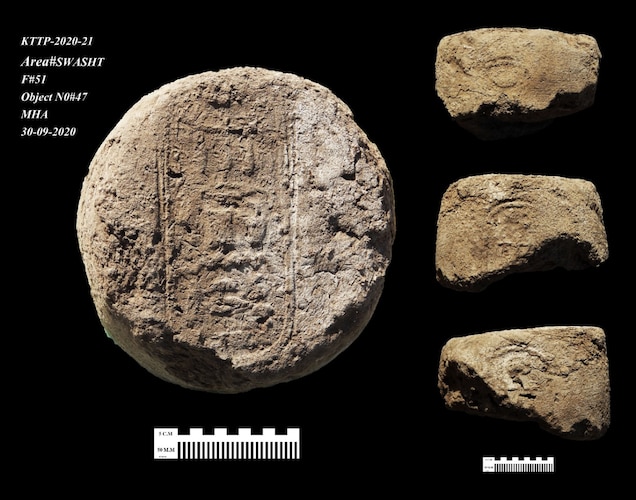

Hieroglyphic inscriptions found on clay caps of wine vessels at the site helped to date the city to the time of Amenhotep III (r. ca. 1386 to 1353 B.C).

Courtesy of Zahi Hawass

Archaeologists had hoped the space between might be the site of the mortuary structure where Tutankhamun’s subjects would have placed the food and funerary items they offered him when he died around 1325 B.C. Instead, they uncovered something very different: zigzagging mudbrick walls up to nine feet high and piles of ancient artifacts from the era of Amenhotep III.

Structures are packed with everyday items, many of which relate to the artistic and industrial production that supported the pharaoh’s capital city. There are homes where workers might have lived, a bakery and kitchen, items related to metal and glass production, buildings that appear related to administration, and even a cemetery filled with rock-cut tombs.

Two unusual burials of a cow or bull were found inside a room in the city. Investigations are underway to determine the nature and purpose of the animal burials.

Courtesy of Zahi Hawass

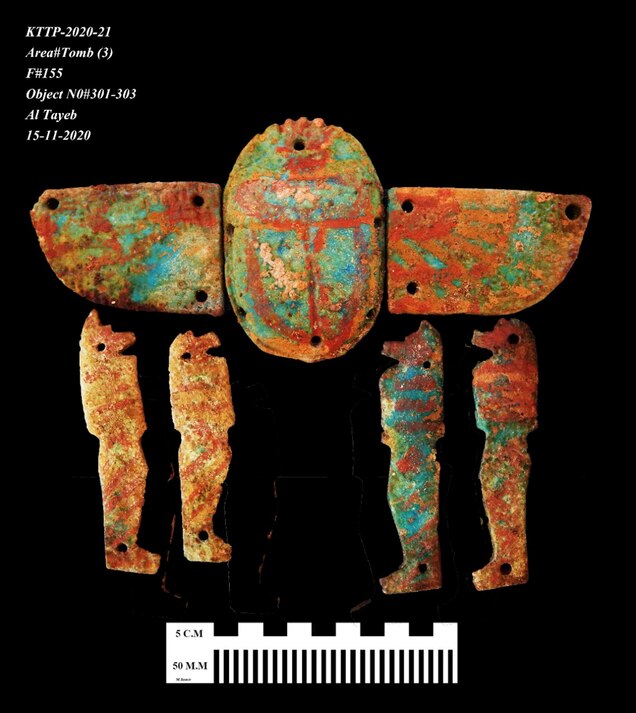

Though the size of the city has yet to be determined, its date is clear thanks to hieroglyphics on a variety of items. A vessel containing two gallons of boiled meat was inscribed with the year 37—the time of Amenhotep III and Akhenaten’s speculated father-son reign. Scarabs, bricks, vessels, and more bear Amenhotep III’s royal seal.

The buildings also bear his soon-to-be heretic son’s name, says Betsy Bryan, a professor of Egyptian art and archaeology at Johns Hopkins University. Bryan, who was not involved in the dig, visited on a day when archaeologists found a small clay ceiling stamped with hieroglyphs that said ‘The aten is found living on truth.’ “That’s an epithet of Akhenaten,” Bryan notes. Despite references to the younger king, though, she says the city is part of his father’s palace complex to the north, which was named Nebmaatre or “the Dazzling Aten.”

Once Akhenaten came into power and changed course, he left his father’s city, and seemingly everything it contained, behind.

That loss is modern archaeology’s gain. “It’s extraordinarily beautiful,” says Ikram. She recalls walking through the preserved streets, surrounded by tall walls where, she says, she expected an ancient Egyptian to come around the corner at any moment. “I don’t think you can oversell it,” she says. “It is mind-blowing.”

Archaeologists have found an abundance of decorative and ritual items, including scarabs and amulets.

Courtesy of Zahi Hawass

The city appears to have been reused by Tutankhamun, who ditched Akhetaten during his reign but established a new capital at Memphis. Ay, who later inherited the throne when he married Tut’s widow, seems to have used it, too. Four distinct settlement layers at the site show eras of use all the way into the Coptic Byzantine era of the third through seventh centuries A.D.

Then, it was left to the sands until its recent discovery.

But why was it abandoned during the brief reign of Akhenaten? “I don’t know that we’ll get closer to answering that question through this particular city,” says Bryan. “What we will get is more and more information about Amenhotep III, Akhenaten, and their families. It’s early days, but I think we’ll see more and more connections.” Though the newly discovered city may not give up clues to the mystery of the rebel pharaoh, it will paint an even more vivid picture of the life he left behind.